After the Death of My Father, I Now Carry His Dream of Freedom

Anya Gillinson reflects on her father's defiance of Soviet oppression, his Jewish identity, and the lasting legacy he left behind after his tragic death in New York.

Editor’s Note: The last time we saw true Jewish unity was during the campaign for Soviet Jewry, when Jews from all political backgrounds came together for a common cause. In today’s divided climate, particularly in the United States, we could learn valuable lessons from that era on how to work together. In this essay, author Anya Gillinson, who was born in Moscow, reflects on how she learned from her father to be both a proud Jew and a proud American—something worth remembering during this contentious election season. — Howard Lovy

Thirty-four years have passed since my father’s brutal murder, and so much has changed in this non-poetic world, but I still look at life through my father’s eyes, not only out of a daughter’s loyalty, but because he was a true dreamer, a real poet at a time and in a country where dreams and poetry were an anathema.

Soviet Russia sought to destroy men like my father. Yet, my father was not like most Soviet men of his time. My father’s spirit would never submit neither to the Soviet system nor to any other known authority. He was a visionary, a maverick. My father was neither good nor bad, neither gentle nor hard, neither sensitive nor superficial. He was a great man, with all the flaws and complexities that inevitably come with a truly charismatic personality. A brilliant diagnostician and physician who had invented a method of successfully treating bronchial asthma and other pulmonary and cardiovascular conditions not treated in the Soviet Union at the time, he became known as Russia’s unofficial miracle doctor. Though erudite, he was continuously unsatisfied with the knowledge he received from conventional sources.

In the 1970s, already in his thirties during the period of Soviet stagnation, he hired an American to teach him English. It was a most unusual thing to do at the time. He wasn’t just interested in learning how to speak the language, but he wanted to understand the psychology behind it. Freedom was a concept totally foreign to most people born under the Russian sky, but not to my father. Born during World War II, his childhood unfolded in a country ravaged by revolution, wars, and repressions. Growing up within a society duped by propaganda and gripped by fear, isolation, and a constant sense of enslavement, my father's mind instinctively rejected the entire Soviet paradigm. Even as a teenager, his mind sought questions, not answers. He dreamed of a life of wealth, freedom, and adventure, not of poverty, enslavement, and sameness.

He defied every rule and regulation the Soviet regime had imposed on its doomed citizens. As a young doctor he decided to challenge one of the greatest taboos of the socialist order: one shall not enter any business for oneself. He opened his medical practice straight out of his and my mother’s first apartment not long after they got married. He made no secret of it. Nothing could stop those flocking crowds of desperately ill patients; my father was their last and only hope.

He treated everybody: the poor and the rich, the old, the young, infants, teens, invalids, peasants from collective farms, members of the Soviet elite such as diplomats, party members, Nobel Prize winners, renowned actors, singers, musicians and dancers, as well as mediocre government clerks, policemen, firemen, former inmates, prostitutes, bad people, good people, priests, relatives, foreigners former political prisoners, refuseniks, teachers, and countless others. People waited months, sometimes years, to be seen by him.

He received threats, but he was not afraid because those who threatened to inform on him soon ended up sitting across from him as his patients. He was convinced he was doing the right thing because his main calling in life was to ease people’s pain, and he did exactly that.

My father held me spellbound as a young girl. I saw the world, I understood beauty, and the essence of myself through his unassuming wisdom. He was the one who first announced to me with pride that I was not Russian but Jewish. He identified for me that intimate connection between my Jewishness and the land of Israel. In the USSR, a mere mention of Israel could get you denounced, your past erased, and your future obliterated. Yet, he unapologetically repeated to me that Israel was my true home and the core reason behind every Jews’s survival in this world.

My father rejected Soviet propaganda aimed at fostering hatred and fear of America. Instead, he was taken with the country's vastness, its customs, its promise of freedom and equity. To him it spoke of excellence. In our apartment, there hung an allegorical painting titled “Silence is gold.” On it was the face of an old one-eyed woman with a veiny finger pressed tightly against her blue lips as if whispering to us all: “Do not speak, for air itself has the power to hear and implicate everyone!”

In America, he said, one could never be punished either for speaking up, or for choosing to stay silent. To a Soviet species, this was an inconceivable and wicked notion, a dream, and a poem, woven into one.

And so, from the time I was six, I began to dream of entering this land of immigrants, puritans, reformists, conformists, idealists, loners, and dreamers. At the risk of being expelled, I used to tell everyone at my Soviet school how one day I was going to emigrate to America and live in the glistening Manhattan where I could stand in the middle of the street and criticize presidents without being punished for it. My father promised me this on every poetry walk we took together. Eventually, his promise came true. I have lived here for over thirty-two years now, and from time to time, I do criticize American presidents.

America! For some you shall forever remain nothing but a promise of freedoms, miracles, and audacious dreams. The mythical, gawky city my father revealed to me years ago became both the fulfillment of my dreams and a haunting symbol of loss and heartbreak. That summer of 1990, my parents left my sister and me in an exclusive resort near Moscow and flew to New York. Father was murdered there five days later during a random robbery, while shielding mother from a twenty-three-year-old attacker by the name of Eric Wilson.

It was a quiet, starry night. My parents, returning from a night out in bustling Manhattan, reached their friends' home in Forest Hills. “How peaceful,” my father remarked as they approached the building. Then, in seconds everything changed.

A man accosted my mother, demanding her purse. My father intervened, shielding her and rushing them inside. The assailant pursued, firing a shot that struck my father. He collapsed, protecting my mother with his body.

My father was lying on top of my mother, covering her completely with his body. It got quiet again. My mother felt no pain, but the clothes she was wearing began to feel sticky and wet. She looked around and saw she was sitting in a pool of spreading burgundy liquid. And then she saw him, my father, her Arkady. She understood that it was his blood. In agony, she began to scream. The bullet tore through his vital organs—heart, lungs, and liver—before miraculously lodging in his elbow, sparing my mother. He was pronounced dead upon reaching the hospital.

From the shock and grief of it all, my mother had lost her voice. It had only happened to her once before, on their wedding day. She was happy then.

Could I still love America? New York City? Freedom seemed vacuous without him. Has his dream betrayed us both? Decades later, for different reasons, America has changed, and so has my beloved city, having endured one of its existential metamorphoses and proving its resilience to an exasperated public. Would today's New York, with its post-pandemic duskiness, stressed economy, untidiness, and unfathomable wealth, still take my father’s breath away like it did all those years ago? I don’t know. But I do know what my father knew as well.

America still holds on to one of its most important intrinsic elements, deeply rooted in its very soil, that no force can ever eliminate. Gradually, this country's innocence has been chipped away at. Even so, it never gives up on regaining it, embracing anew its ideals of fairness, justice, freedom, and the right to happiness. Perhaps it is this very relentless attempt that makes others dream about this country. Perhaps this is why, after so many years, amid the most prosaic reality, I can still hear poetry in what was once my father’s dream.

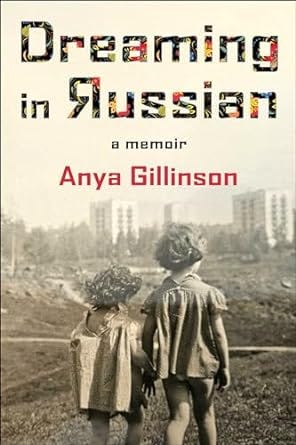

Anya Gillinson was born in Moscow, Russia, into the family of a renowned physician and a concert pianist. When she was thirteen years old, her father was killed during a botched robbery on his first and last visit to New York. Two years after his death, Anya moved to New York with her mother and younger sister. She went on to graduate from law school at Pace University and is an immigration lawyer who has counseled and helped primarily professionals in the fine arts. However, it is literature that has always been her true calling. In 2015, she published a volume of acclaimed poetry in Russian, Suppress in Me the Strive to Love. She recently released her memoir, Dreaming in Russian, which Forbes called "spectacular." Anya now lives in New York City with her husband and two daughters. More at www.anyagillinson.com.

Five Tiny Delights

Low-fat or fat free Frozen yogurt and lowfat ice cream from my local sweet shops

Russian honey

Sushi, sushi, sushi

All sorts of Russian preserves and jams

Fresh raspberries

Five Tiny Jewish Delights

Gefilte fish

Herring

Israeli salad

falafel

Israeli humus

This wildly beautiful essay electrified me. My husband was like your father. Since childhood, he despised his native homeland of Russia and burned to be an American to the marrow of his bones. He arranged to be an exchange student for a single semester as a freshman in college. There was a funereal silence in the car as his family brought him to the airport. It remained totally unspoken but fully understood by everyone that he would never be back.

Two months into his exchange student experience in upstate NY, the Russian economy collapsed and his parents could no longer afford his tuition. He would soon be broke and homeless. He was 17 and totally alone in a foreign country, with no contacts, no money, no livelihood, no friends or family, no English, no nothing.

Over the weeks and months and years ahead, he would sometimes go without a mouthful of food for 6 or 7 days on end but he never once considered going back.

On the other side of things now, he was able to bring his parents over. My father-in-law is a Ukrainian nationalist, and he too would rather die under a bridge in America than live in a palace in Putin's Russia.

I pray that in another week, we will vindicate the choices of brave men and women like them by keeping democracy and freedom alive here.

Thank you for exposing me to authors I might not have known. I'm a bit overwhelmed.

Nancy Shiffrin https//www.NancyShiffrin.net