Burn the Boats

An excerpt from A. Jay Adler’s memoir 'Reason for Being in the World' revisits his father’s decisive flight from Ukraine.

Editor’s note: I’m drawn to essays that rescue family history by stepping into its missing rooms. In the excerpt below, from Reason for Being in the World, A. Jay Adler reconstructs the day in 1920 when his father, Meyer, and aunt Golda slipped out of their Ukrainian shtetl. Every scene rests on family testimony, archival digging, and informed imagination; the dialogue is recreated, not invented from thin air. I used the same approach in my own account of my grandfather’s experiences during a pogrom in Hungary. Treat Adler’s chapter as creative nonfiction—firmly grounded in fact, written with the urgency of a story that still shapes lives. — Howard Lovy

I had learned intermittently over the years very few things from the taciturn Meyer about his childhood in pre-revolutionary Russian Ukraine. At the end of the day, he watered his grandfather’s horses by the waterfall at the lake. Once, in the dark there, dad had been frightened by the full moon and run up the hill through the trees to escape it, but discovered that it always followed wherever he went. During pogroms, Zakiah had led the family up among the same trees, through the Jewish cemetery, to the home of friendly Ukrainians, who hid them.

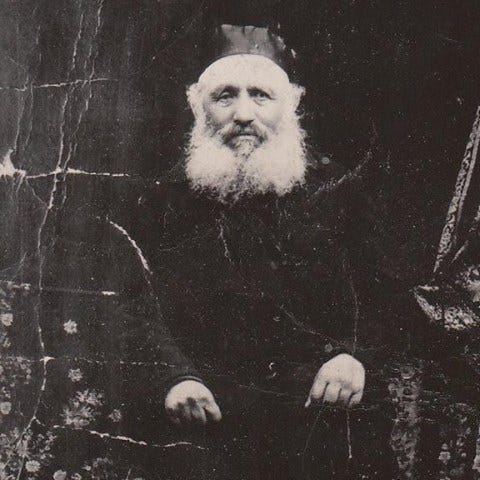

Who was Zakiah? I have the one photo. He had four living children. One daughter, divorced, left her children behind with him and his wife to start a new life in America. Another lived in Kamianets-Podilskyi; a son in Lviv with his Romanian wife. Aikah, the youngest, helped care for her niece and nephew, Golda and Meyer, after their grandmother died. Zakiah bore his responsibility: he cared for the lives of his daughter and another daughter’s children. Too old, too traditional, too uneducated, probably, to be a Bundist, was he pious? Or was he one of those dissenters who on the Sabbath, on the holidays, worshipped alone for his own reasons in the lean-to, side addition to the Old Shul, the “cold shul,” that no one alive could remember being built or how or by whom?

What else made up the poor balagula’s life, his children mostly gone, besides the care of his eyniklech and the long daily trips with his passengers over rutted roads? Did he visit his wife’s grave each day, just up the hill? Did Zakiah, after all were asleep, sit by a window with a candle for some last, quiet waking minutes and… write?

Did he argue with Jews on the streets of Kamianets, after dropping off a fare, that there would be no Messiah because there was no God, because even if there had been a God, he had been murdered in the shtetls of the Pale a thousand times – a hundred thousand times – the Bal Shem Tov be damned, and maybe that’s why our father never went to school, besides the war all around them, because there were only the Jewish schools, the cheder, and Zakiah, almost everyone gone from him now, was too poor to afford them. He wouldn’t take the town charity of the high and mighty balebatim who rode in his wagon but wouldn’t marry their children to his son or daughters. To hell with them, anyway, they taught two thousand years of nonsense, put a horse’s reins in your hands and you’ll live.

But Zakiah dies. Mac didn’t remember how. Had he ever known? In a pogrom – one of the hundred thousand? From a heart attack, the Ashkenazi affliction that nearly killed Mac, that killed my brother, my mother’s brother. Face down in the dirt one day, no one knows what. All Meyer and Golda know is he’s dead. He’s gone.

Now, it’s Aikah, maybe only 18 or 20 herself, alone with the two children. It’s 1920, the Revolution won, the Civil War won, Ukrainian nationalists on the run, but pogroms killing Jews everywhere, the Soviets, now occupying the town, upending everything. Young Jews are among them, turning on the old – and with the poor seemingly ascendent, turning on the Russian landowners and the balebatim, too. The old order is gone, the Jewish one too. Danger is constant.

Aikah, the children must leave or they will die. You have to make them understand, and even if they don’t. Send them to America. Let them find their parents. Look after yourself.

There were these separate bits of information I had known from Mac for years, without context and with little story, occupying space in my mind, doing no work: Mac and Goldie spent four years surviving on their own in Poland. They went at one point to stay with their uncle in Lviv, and the uncle’s Romanian wife did not want them. The day they left Orynin, they were rowed across the Zbruch River in the darkness of night.

I studied old maps.

In a decade of constant warfare throughout Central Europe and Western Russia, land changed hands often, nowhere more than in northwestern Ukraine and southeastern Poland. And in 1920, the famed and beauteous Ukrainian city of Lviv did not lie in Ukraine. It was in Poland.

With a negotiated border between them along the Zbruch River.

While the common route of Jewish emigration to Palestine ran out of Odessa, Jews heading to the United States usually traveled by rail through Austria-Hungary and Poland to German ports: Hamburg, Bremen.

So Mac and Goldie had been sent to their uncle in Lviv en route the United States, which meant crossing the Zbruch River, putting them in Poland, where something went wrong. Their uncle’s wife did not want them.

But they were two children alone, on their own. How could they even have left?

Zakiah owned horses, a wagon, for which Aikah now had no use. She sold them.

To a Jew who had been a regular passenger.

To a Ukrainian: once, returning from Kamianets-Podilskyi, Zakiah had warned him of an impending Soviet inspection for illegal crop growth; the Ukrainian in return had hidden the family during the last pogrom, when Zakiah had led them on faltering legs up the hill, through the Jewish cemetery, ahead of the Cossack horses.

The Ukrainian would not risk aiding the children himself, but he would lend the horses and wagon to Moishe, the poor simpleton who worked in the barrel factory attached to Zakiah’s stable. But he must be back by nightfall. Anything might happen after dark, and he had paid good money for the horses and wagon

Preparations were made. One of the Sherrels – who lived next door to the horse yarid, the market, perhaps the father of the Sherrel Aikah would one day marry, the Sherrels who would still be remembered in 2005 by the one man left who had only, once, just been married to a Jew, father of Joseph, who fifty years later, landed in America, would show Meyer’s youngest child how to drink his vodka in one shot, followed by a rye bread chaser – one of the Sherrels had contacted a man (he wasn’t a Jew, and he required payment, but he would do it) who ferried people across the Zbruch River into Poland at night.

The day they left, with commotion in the streets and alleys, new rules daily from the local Soviet and frequent rumors of new attacks on Jews, Aikah made up sacks of food and bundled the children’s clothes. The night before, she had talked with Golda: she was older; she must take care of her brother.

They rose before the cock’s crow, Moishe already outside dozing on the wagon. Aikah would not travel to the river, 50 kilometers away, a full day there and back over broken earth pounded smoother by hoofs and wheels, deep into tree cover. She would close the door and try not to remember too often the parents now dead, the sister gone to America, the nephew and niece to whom she had given her heart. She would write again to her brother in Lviv, her sister in Kamianets-Podilskyi, though she already knew herself what she must do. She must marry as quickly as she could, before she became desperate. With no dowry, still she had the house, meager hut, and it contained her mother’s pripetchok, her pride of an oven. Aikah would offer it all to Abram, who owned the barrel factory. He would give her a fair price.

At the door, she straightened Meyer’s jacket, tugged hard on the little boy’s lapels as if to fix him to the ground so he couldn’t really leave. He was so quiet and dutiful, staring expectantly at her. Golda waited, watching, already out the door. Aikah glanced at her, then back at Meyer. They looked so much alike, the boy with his reddish-brown waves, the girl with golden-red hair like her mother, Meyer with his sweetness, Golda a little masculine, with a bulbous nose.

“Remember, what I told you,” Aikah said to Meyer. “Don’t fight with your sister, and even if you do, you must forgive her right away. You have only each other now and no one else.”

Meyer stared. Aikah shook him a little with love. So few words. They had been taken from him.

“Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“Let nothing come between you.”

Tying a scarf around his neck against the river cold and the cold to come, she took his face in her hands and framed it to remember; she might never see it again or not for fifty-eight years in a terminal of JFK airport. She kissed his forehead, closed her eyes, then pushed him away. Go.

Meyer and Golda threw their bundles atop the wagon and climbed up behind Moishe. They looked back at Aikah, her hand at her mouth. Moishe flicked the reins. Aikah cried out.

Running around the other side of the wagon to Golda, she reached up and held the side of her niece’s face.

“My fierce Golda.” She kissed the girl’s hand. “Stick to him, to each other. Protect him. Let him protect you.”

Golda nodded. Aikah came around the other side to Meyer. She looked up at Moishe and lifted her head. The horses started.

“Meyer, sheyn bubula, look at me.” Meyer looked as the wagon pulled away.

“Keep looking. Don’t stop until you can’t see me anymore.” She watched them move on. “I’ll still be here.”

From the forked road where their small clay house stood attached to a cooper’s factory, the wagon trundled toward the Post Road in the dawn’s light, Meyer gazing back at his aunt.

“Golda! Meyer!” he heard called out, “where are you going?”

“To our uncle in Lviv,” Golda answered, and Meyer swung around to look at Lev, the cooper’s son. They all stared at each other. When Meyer swiveled back again, they had already completed the turn onto the Post Road, and Aikah stood visible no longer.

All down the Post Road, through the center of Orynin, Meyer saw the merchant’s houses pass, the side, market streets begin to bustle – no more looking back at the only life he and Golda had ever known receding from them, everyone they had ever loved receding from them, except for each other.

The town square passed, the post office and flag pole, with its new red flag on it, and then they were leaving the town. Golda wrapped her arm around Meyer’s shoulder. He shook it off without looking at her. Golda stared at him. Gently, she petted the back of his head, then withdrew her hand and placed it in her lap to look forward.

The 50 kilometers were long and rugged, and what receded in the bone jarring distance felt an ache so deep and broad in the body that in time, was it months was it years, it could not be located or even recognized as pain anymore. It was in the sinews, and in the life to come, when the ache swelled up again suddenly, in a flash of rage or a bitter, painful mistrust, it growled like a wounded animal roused from a curled and nestling self-comfort. Before the stick’s poke – a disregard, a disrespect – it had almost forgotten the hurt.

Moishe drove slowly, uncertainly, arriving late, nearing dark. He must turn right around. The Ukrainian would be angry. Almost still a boy himself, Moishe held out his hand.

Good luck, Meyer. Good luck, Golda. Maybe someday I’ll follow. They say in America, a Jew is treated like anyone else. Now that would be a place to see!

But Moishe did not follow. It had taken time – he was no woman’s prize catch – but he married and had two sons. To emigrate with a family, with young children, was a hardship he could not imagine, a transformation of her world Shayndel did not wish, so he made the best life he could for all of them. In the new Soviet world, Moishe was a little less Jewish, though privately they still kept the Sabbath and the boys studied Torah. Until sometime in August 1941, when all the Jews of Kamianets-Podilskyi were executed by the just arrived Germans, Orynin, too, was occupied, and its Jews confined to a ghetto. Ten months later, in June 1942, a Nazi Einsatzgruppe ordered that all the male Jews of the ghetto assemble in the town square for work assignments. The Ukrainian auxiliary police called out, knocking on doors, and soon Moishe and his two sons were walking among several hundred other males along the Post Road.

Someone in the crowd wondered what labor the Germans would set them to.

Another said, Fool, have you not heard the rumors? The stories of those fleeing across the countryside all around us. There will be no labor, today or any day.

You are such a pessimist, Yisroel. Always thinking the worst. Why should they kill us? We haven’t opposed them. What would it achieve? They need us, better, to work.

Moishe did not speak. He rarely spoke. They always laughed at him when he spoke. But while the others argued, he spied from the corner of his eye a figure running along the eastern tree line. He squinted carefully through his spectacles. He wasn’t sure, but it looked like Goldfarb, bending and darting furtively as if an animal. Then he was gone, lost in the trees. Moishe looked back at the slowly moving crowd. It didn’t appear anyone else had noticed.

Moishe hung his head. He did not think the Germans were going to put them to work. No. He did not. They were all going to die. That day, they were all going to die. He might flee now himself if he could find the will to act he had never found before, if the police did not line the road, their rifles pointed at the passing Jewry of Orynin. So there was no flight to be made. And there was no denial by which to fool himself. Moishe Mandelbaum would die that day. He and Yankel, to his left, number one student in the secret Talmud Torah school, and Yossel, to his right, already calling himself a socialist, they would die. And who would remember them? Shayndel would remember them, that’s who, his beloved Shayndel, who had loved him when no one else had.

Unless they killed her too, maybe tomorrow. Oh, my wife! Then who would remember? Who would remember any of them?

Ah, why hadn’t he left when he was young, as he said he might? Why hadn’t he left – like Meyer and Golda all those years ago at the Zbruch River? What had happened to them? he wondered. Had they soon perished, been dead themselves these long years? Or had they made it to America, living lives without fear? Aikah had married and left Orynin, so he never heard. Oh, why wasn’t he in America? Why hadn’t he gone when he might have gone and been free himself?

Moishe squeezed more tightly the hands of his sons, winced his eyes shut. Oh, my God, you are a cruel God – to make me choose between the life I had wanted and the life I had, with my beautiful wife and sons, though we die here today. To make me wish it. To make me choose this death because life without them would be no life at all.

Moishe raised his head then, aware suddenly of all around him, though he saw none of it. He was in his thoughts, a dream realer than real, though reality was like a dream. They were nearing the square, walking slowly forward, the police lined up and waiting. Together – they were so alike – Yankel and Yossel glanced at him. And for the second time in his life Moishe Mandelbaum knew dread. Dread that sank within him to the earth – knew even the taste of dread. It tasted like sea salt. Like the salt of the Black Sea, which he had actually seen the year before he married, in the great adventure of his life (yes, he had had one!) when Victor, whose father bought the barrel factory, then tore it down, whose grandfather had been among the last of the Chumaki – when Victor challenged Moishe to journey with him, and Moishe had actually swum in the Black Sea and nearly drowned.

He remembered the gathering dread he had felt then, thinking he was about to die, how he could see the world, still, through the wavering, watery glass of light at the surface of the sea – how the water washed into his mouth – bitter, salt water – and how, thinking he was going to die, he could have reached his hand toward the clear surface of light that was the world, that was the school house before him, though it grew dimmer, dimmer and farther away, until it was sixteen years later, and what he thought he had escaped had been waiting for him, oh, look, it had been waiting for him all these years . ...

Meyer and Golda stood alone at the appointed spot – they hoped! – along the Zbruch River, awaiting the appointed hour. They remained hidden within the tree line so no one would wonder why a boy and girl waited at the river as night approached. It grew dark, truly night. They tried not to be scared. They were scared.

At last the boat arrived from across the river. The man at the oars, was he a Pole? He spoke Russian. Who knew? He was not mean or even brusque, but matter-of-fact, like it was business. Where was the money? he asked. Golda offered it, separate from their other money, so he would not see. (Aikah had directed them.) Would he beat them – a full-grown man, a hard man – and steal their money, take them nowhere? How long would it be before they were free of such fear in their lives?

The river man helped them into the rowboat. Then he stepped in and pushed off with an oar, turning to face them as he settled onto his seat, his back to the opposite shore. He stared at the two children. Golda wanted to hold her brother, but she did not. She did not want to appear afraid. She stared back. She didn’t think the man was Jewish, so rather than Yiddish, she spoke in Russian, as he had done.

“Please, sir, take us to Poland now,” she said.

The river man looked expressionless. He began to row.

Soon, they approached the middle of the river. With no moon – the plan – it was black all around them but for starlight, like just after Zakiah would blow out the lamp. Night had fallen over the world. The river man rowed with long, deep, dual strokes, his back strong, his purpose to reach the other side and be done. Meyer remained as still as he had been all day, but he saw the cold water streaming beside the boat, and as any man might, but surely any boy would, he dipped in his hand to trail it in the darkling waters, following with a backward gaze the fingerlet waves. He watched them disappear.

Meyer had no words to form for himself his thoughts, no experience by which to know his unschooled emotions, but he wondered in some vague way, glancing back, what it was he had come from, to where it was he was going. So blank it was, he felt to be going nowhere at all.

Somewhere in the middle of the Zbruch River, along a border between Poland and Ukraine, eighty-four years before he would die in the intensive care unit of West Hills Hospital, in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles, California, the boy who had tried to run from the moon stared up into the sky, and for a moment the world stopped, stars unblinking and oars suspended in air.

Meyer sat poised between two shores, a boy held in the full suspense of every fate that might be his, all the possible futures that swirled and eddied invisibly around him: our father, long before he became our father, before he was the man who could become a father, coming to us as a boy, slipping through the stream of possibility in which at any instant he might drown. Though the boy did not know it, Adolf Hitler was soon to rise in Germany; Leon Trotsky, not many miles away, would lose, after winning, a revolution.

But Meyer was just a boy on a river, as there have always been boys and girls on rivers, crossing perilously, far from the dim reaches of power, where the world is made and remade from ideas and forces into forms for which the young can have no care. The stars, the boy thought in that moment, seemed so far away. And what were they really? He didn’t know.

Then my father caught a scent from the distant shore. Honey, it seemed, sweetening the soft night, but something else, too, he couldn’t place. He turned his head toward it, up toward that far shore. Golda turned to follow his gaze, placing her hand on her brother’s shoulder …

… and the stars began again to blink, the long-forgotten river man again began to row, a nameless oarsman pulling the boat's paddles, plashing in the moonless night, stroke after deep stroke, tugging them forward, beating on, beating on, bearing them swiftly on the human current, drawing them without recourse into the future.

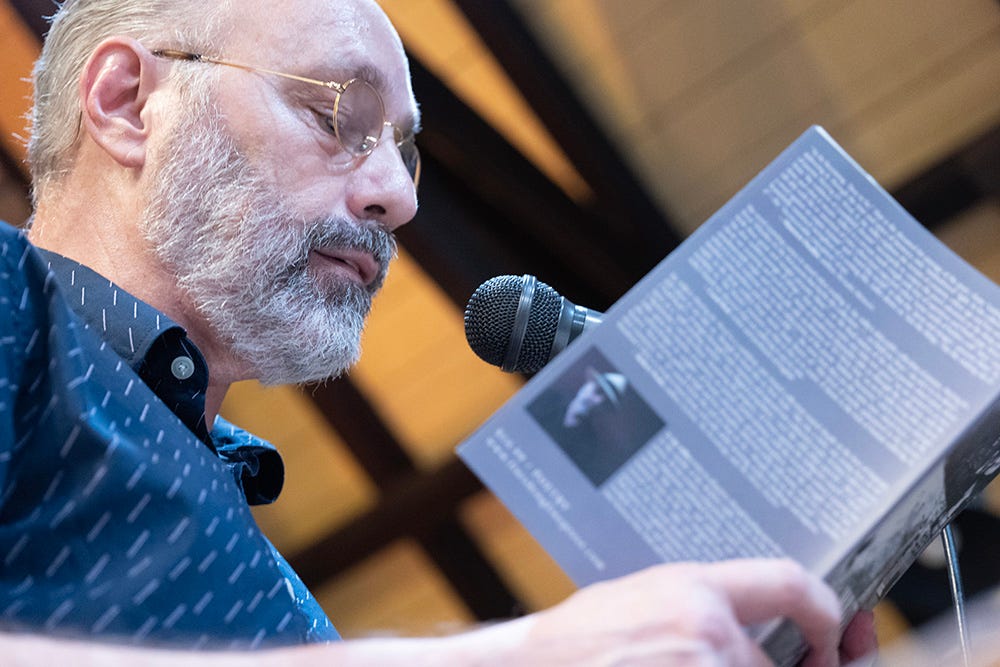

A. Jay Adler is the author of the 2021 poetry collection, Waiting for Word, published by Finishing Line Press. He also writes memoir, fiction, drama, and essays. He has won awards in screenwriting and a Vermont Studio Center residency grant in poetry. He was a featured author of the 2015 anthology Footnote: A Literary Journal of History. Current projects include a historical novel of the Ferdinand Magellan expedition and a California crime noir. A professor of English for over thirty years, Adler publishes weekly on his Substacks American Samizdat and Homo Vitruvius, where he is now serializing his play, What We Were Thinking Of..

Five tiny delights

1. Long walks and hikes, in nature or along city streets.

2. The ocean: cliffs and beaches, sunlit, sunset, or fog-covered.

3. Dogs and sharing with them the simple joy of living and playing.

4. A good whiskey or brandy, especially combined with number 2.

5. The sweet-tart, crisp-light perfection of Honeycrisp apples.

Five tiny Jewish delights

1. Eating deli. (I’m a deli Jew.)

2. Jewish comedians.

3. Sitting around cracking wise with other bald Jews.

4. Remembering the Jewish world of my childhood.

5. Just the feeling of pride, when it arises, in being Jewish.

Dear Professor Adler. Thanks for the wonderful piece. My late father was born and raised as a child in Kamenets Podolsk and so the name of the place alone has a special place in my heart.

Jay, I am SO happy to see this excerpt in Judith. Congratulations!

I think I've read this particular piece of your memoir at least three times, and each time it comes more alive, more visual, more lyrical, the yearnings and farewells more bittersweet, the dialogue "right" in the ear, the history more telling (because we know it). It reads so beautifully here. I continue to be taken by the passage relating the crossing of the river at night and the moon that must be run from, and that need not to be seen. The foretelling and foreboding both are strong throughout, and yet there is the hope in the journeying, or as your title evokes it, "reason for being in this world." I am struck by how much currency this memoir has at this time of our lives; the images this chapter paints, we see them today on our front pages and computer screens, history repeating itself, looking back and imagining what's ahead.

Thank you!