Dybukky

Dybbuk: a wandering soul believed in Jewish folklore to enter and control a living body until exorcised by a religious rite (Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

Editor’s Note: A short story about the many ways one can be consumed, by up-and-coming young author, Charlie H. Williams —David Michael Slater

Ephraim Moses Lilien’s Dybbuk

I think it's like a dirty word when you come up behind me at the party and wrap your hands around my chest and lay your head on the back of my neck. I feel guilty for thinking it at once and move quicker to hold your hands there in mine, against my chest, so you’ll think my pattering heart is because of your touch and whatever drugs I have in me. Furtive gesture, as though resting your head against my spinal cord could transmit the word to you, shivering from my nerve impulses to blossom, snitch, and traitor, in your brain.

Dybbuk.

I am disquieted. I drift from you. Talk empty subjects with anyone I don’t recognize already. There’s a girl by the drink table, also Jewish, with black tunnel earrings and a garish Hamsa pendant on a chain around her neck. She starts jumping up and down and saying Oh my Gawd when I explain what it is I paint.

“All Jewish mythology? All your work?”

All, yes.

“Golems and Lilith and those ghost things, right?”

Right.

“That’s so cool. My Aunt Sharon had a real dybbuk box, if you want a picture.”

No, I’m fine. (Dybbuk boxes are an internet scam and don’t deserve a charcoal sketching, much less a painting.)

“Wait, wait, wait. You have to see this.” She pulls out her phone, nearly fumbling it out of her sweaty hands and into her murky drink, in her haste to pull up a picture of a snuff box embossed with a woodcarving of the Lilien illustration I’m committing to canvas. The one with the traveling soul bent double over his walking stick, crushed by the weight of the skeleton draped over his back. Both dripping black rags. Spine to bare spine. One of the skeleton’s legs jammed against the traveler’s backside like the pose of a too-cool-for-school bad boy, a one-legged heron, a burlesque dancer in their kicking throes.

The woodcarver fucked up the detail work, of course. The traveler’s cloak should be inset with whorls, like the language of a fingertip, but the shroud is uniformly flaccid and smooth. The hand not gripping the stick holds the skeleton by its radius bone, but it should be held by the humerus. Worst of all, the traveler seems to be wearing shoes and peasant clothes beneath his burden. Half of the illustration’s intimacy, its allure, lies in the exposed flesh of Lilien’s second-most-nude model. All to indicate that Aunt Sharon’s ‘real dybbuk box’ was more than likely crafted by a sloppily-pirated JPEG and a machine-mounted laser.

The Jewish girl is grinning at me as though she expects me to snatch her phone and start drooling over the cheap copy on the screen. My head begins to pound.

Excuse me, I think I’d like a smoke.

She wants to come and keep talking about my work, so I tell her I hear you calling for her (I do not). While she searches for you, I stumble out to the balcony and lose my stomach over the iron railing. What comes up is mostly clear and smells of vodka and lemonade, which is all I’ve had in me since midday. I smoke to mask the taste and smell of vomit, and come back inside and find you and kiss you, because you like the taste and smell of cigarettes. This is good, for a bit. I stick out the rest of the party, and the cleanup, and the post-party smoke with your friends, and bedtime sex with you.

But I think the word again when we’re lying together, when everyone but your visiting friends are gone and it’s just us in your bedroom, lit like an aquarium by the lava lamp on the far dresser. My back is to you because I get overheated when I hold you. You’re holding me, which you’ll do until either you fall asleep like that and I get uncomfortable and worm out, or I fall asleep and roll away in the course of the night. For now, your belly is pressed against my spine, and I can feel your breathing, your heartbeat. I know that if I crook my hand behind me and trace your back with my fingers, lock us like that, your hand around my chest and mine against your vertebrae, you’ll shiver in your sleep. Your breath is cloying in my ear; perhaps you vomited earlier, too, and didn’t tell me. I won’t ask you tomorrow. I’m glad for things like your bad breath, the warmth of your flesh on my back, tangled limbs about me. All of these things mean you are alive against me, and the word that continues to appear in my head, incessantly, does so only by the coincidence of correlating positions and stubborn mental images. I have been researching too much for the painting, and you have been at my back all night. So, dybbuk. Dybbuk. Dybbuk.

That guilt again. Why should it make me feel guilty? Long hours at my studio? I’m with you now, though, aren’t I? Chas v’shalom, I dedicate time to the passion project, paying my Brookline rent, paying for nice things for you! I know too well the danger of resentment, of feeling caged by a partner, but that’s not what this is, no. You’ve done nothing wrong. This is a language trick, I could explain to you if you were awake, and I wanted to explain such a thing as this, which I don’t and wouldn’t. It’s a trick that, by the etymology of a tongue hardly my own past Sunday school Hebrew lessons, can mean several things.

It can mean to cleave to, stick to, latch on to. Glue is dybbuky. Crazy exes, sure. Spider silk. Tree sap. Wet concrete. Chewing gum.

Or, yes, it can mean exactly what it is in either language: Dybbuk. Clinging spirit. Obsessive soul. Possessor. Fewer analogies for that one.

I sleep and dream a conjoined version of us, you fused atop, legs belted around my waist. Your arms are wrapped over my shoulders like book bag straps, each broken at the elbows. The conjoined thing scuttles about on my fingers and toes, on the tips of my fingers and toes, and can leap great distances like a dog tick. It sights me and bounds my way, hooting words that are not words at all.

I wake up trying to flatten myself away from it and find myself smothered in the sheets and your embrace; it seems I’m freed only by my sweat, which slicks my body and dampens my side of the bed. You’re still asleep.

I’ve got one cigarette left, and I take it and step onto the chilled front porch, pulling one of your threadbare flannels around my shoulders. The sky hangs low and heavy, tethered to the apartment roofs by coils of chimney smoke. Cloud swells, pockmarked like hammered copper, squat overhead. The moon is reduced to a pale thumbprint behind the bedded smog cover, the stars to nothing at all. All the street lamps on this side of the street are from the early twentieth century and are gradually purpling with disrepair, humming fluorescent corneas shot through with violet blood vessels.

I sit, shivering, on the bottommost porch step, and am putting my smoke to my lips when the front door shushes open behind me. I think Dybbuk out of habit, but it’s just what‘s-his-face, one of your many friends from home visiting for the party, with nowhere else to stay for the night. He’s dressed better than I for this weather in a loose black hoodie and sweats, but barefoot like me, didn’t want to lace up his oily Docs for a quick smoke. He asks for a light and I stand to give it to him, but the wind’s started up and I can’t get it right. So we step away from the porch and huddle behind the stairway, somewhat shielded, and he tucks his head into my shoulder to provide a cover for the flame, and when it sparks, I become aware of my exposed chest, the budding curls of hair there. Seeking a distraction, I look at him, at the way his cheeks and lips curve and pucker with uncanny symmetry to kiss-kiss the cigarette. He looks like a mugshot of Stalin as a young man, those wolfish cheekbones shaded with charcoal stubble. Soot-eyed gangster belonging to this dark, this cold.

How do you know Jeremy? I ask, because maybe I didn’t ask whenever we met. The question comes too high-pitched, and I look up at your window in case you heard your name, but you didn’t. When I look back, he’s staring at me with those beetly eyes, lit from below.

“Don’t,” he answers. Then, “Lighter’s going to run out of gas at this rate.”

I realize that I’ve been keeping the flame going this whole time, long enough for him to puff his cigarette three times. I pocket it hastily, embarrassed, but the metal is biting hot now, and the pain that comes when it presses against the flesh between my thumb and forefinger is so sharp that I pull my hand out with a yelp.

He’s there at once, squatting for better access to my hand, so I’m inclined to squat too. My ears are hot and numb. He’s turning the burn over in the glow of his cigarette like it’s the most interesting thing in the world. He says around his smoke that he knows how to fix this, and pulls his cigarette out of his mouth, and replaces it with the flesh between my thumb and forefinger. And we sit like that, against the brick wall of your apartment, and then gradually, against each other, my chin against his wiry hair, his mouth around the burn, sucking, licking, tugging the skin long and cold. I inhale through my teeth, and he peers up into me, eyes empty even of wickedness. We are folded together by then, in each other’s arms, against the hideous wind. His lips are warm from my burn, but they shiver anyway when he presses them to mine. All of him shivers greedily, and he arches against me like a hungry shadow, and I pull him down and away for a while.

Where we go is not cold or cracked concrete or violet-poisoned streetlamps; perhaps I dream, awake, of slipping through braids of warm muscle with no start or finish. Then I’m lying on the distant concrete like a caricatured murder victim, getting scrapes on my ass and pebbles in the small of my back as I watch myself keep dazed, spasmodic pace with this coal-eyed boy easing me in and out of him. He is weightless and cold as the wind around. As we complete and he twines back around me, spine against my heaving stomach, I realize he has no smell, not even of cigarettes, and I suddenly long to be out of him and away.

I insist we head inside five minutes apart and offer for him to go first but he just stands there, naked and unshivering, eyes burning into my violet-bathed face, and I feel them burning my back and the flesh between my thumb and forefinger as I turn and leave him there, thinking not for the first time that I haven’t gotten his name all night, not that you ever cared to introduce us. Your old pal from home, What’s-His-Face, who could be any of ten men I met tonight and who never comes in after me. The pile of miscellaneous friends asleep on your floor looks snug and complete; there is no mussed-up sheet or bare pillow, no evidence of a sleeper gone astray.

I come back to bed and fall in beside you, and in your sleep, you drape your arm around me and pull me close, and I let myself be pulled because all my attention has gone to the burn on the flesh between my thumb and forefinger. The burn on the flesh between my thumb and forefinger is a shiny, swollen boil, throbbing longingly. It is real in the way all dreamed wounds are real, and I memorize its dimensions so that when I wake, I can sketch it. It will be unmade through that process. I will draw what I see crawling around inside, the coiled penumbra of the fetal thing backlit in shifting plum and sapphire hues by your lava lamp. The color of the pus to weep from the boil will tell the proper palette to use for my painting. It, born, will be my apology gift to you. It will have my eyes, and your laugh, and his spine, Oh, God. Oh, God.

Your forearm around my neck, gentle, gentle. Stuck to me. Dybbuky.

I stare at the blemish. It stares back. It doesn’t sleep, so why should I? I am sleeping, I remind myself, and wink so it knows I’m only joking. Perhaps it will give birth if I stare long enough. Like how Pegasus crawled, fully formed and slicked with embryonic slime, out of the bubbling stump of Medusa’s neck. This thing, the crawling thing in my boil, wants to be born again. Already your warmth at my back enrages it, as the impenetrable white landscape drives a man with cabin fever to spitting madness.

His raggedy teeth bared against my cheek as he bobs slower on me, slower. Dybbuk.

I strain my ears, listen and listen, but I know nobody came into the flat after me. So I must know, then, that there is no naked man, scentless as water, waiting for me in the outer night, with his burning eyes to light the way back to him.

Dybbuk. Perhaps if I scream it aloud, I’ll wake myself up. Dybbuk.

Dybbuk.

Dybbuk.

Dybbuk.

Dybbuk.

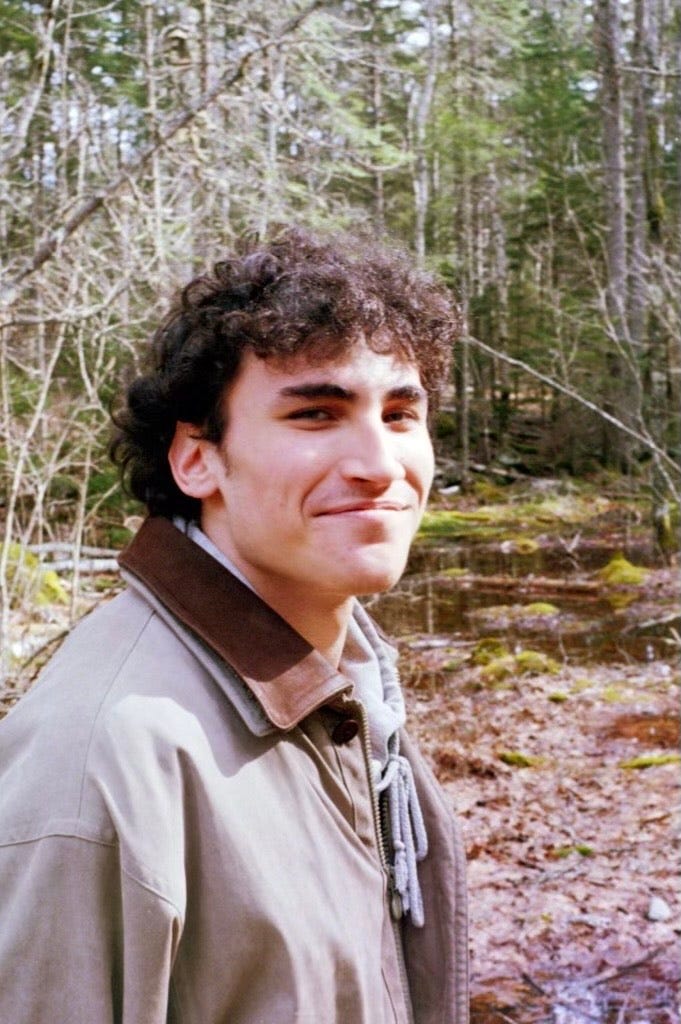

Charlie H. Williams is a fiction writer from Northern Virginia, about to complete his BFA in Creative Writing from Emerson College. His primary genre is literary horror, though he likes writing and reading all areas of the slipstream. He has been published online with Maudlin House and Eunoia Review, and in print with Page Turner, Stork, Concrete, and Collective Tales.

What five tiny delights lift your spirits and make you happy?

Seeing someone’s original art accompany something I’ve written

The spaces between my partner’s teeth

Iced black coffee on scorching hot summer days

Writing until dawn

Seeing my puggle after months away from home.

What five tiny JEWISH delights lift your spirits and make you happy?

Exchanging Jewish jokes with fellow Jews at parties

Speaking terrible Hebrew for my shiksa partner

Seeing my family’s collection of wax-smothered menorahs laid out for the first night of Chanukah

The electric Yahrzeit candle that always glowed above my grandfather’s name at my old synagogue on the date of his passing—I talked with that light as a child, every time I saw it lit

Watching my dog run over for challah whenever someone begins reciting Hamotzi

So consciousness itself--self-consciousness--is the dybbuk. Very, very smart story.