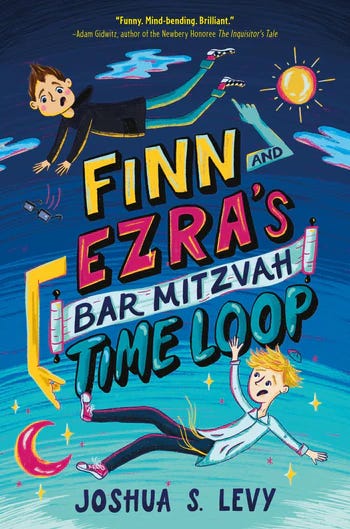

Editor’s note: Having just celebrated my daughter’s bat mitzvah, waiting for the last guests to leave town, it’s like our simcha is never ending too, but Finn and Ezra’s simcha is one you won’t mind repeating again and again. Finn and Ezra’s Bar Mitzvah Time Loop was selected as both the Sydney Taylor Middle Grade Honor Book and the winner of the National Jewish Book Award for middle grade literature and it’s not hard to see why. Joshua S. Levy has written a smart, funny, authentic, and wholly original take on a time loop. Read it. You almost certainly will read it again.

Excerpt from Finn and Ezra's Bar Mitzvah Time Loop, Quill Tree Books/ HarperCollins (May 14, 2024), printed with permission from the author.

Prologue

A door opens.

It’s been a long time (or is it no time at all?). But finally. Finally. Something different is happening. Something new. Someone.

My heart thump thump thumps in my chest, like the second hand of a clock on the last day of school. I reach for him—even though he’s too far away to touch—

stumble forward, face-plant onto the floor.

Questions swirl around me.

Voices close in.

My mom moves to help me up. My dad sprints toward us.

I try to shake them off, escape through the crowd, race against time to the mysterious figure before he disappears . . . before everyone disappears.

Before I have to do this all. over. again.

1 Ezra

My first bar mitzvah took forever.

Friday night dinner was even more of a disaster than usual. We hosted the meal at our house after shul, just our immediate family and a few of my best friends—and everything that could have gone wrong, did. Barely enough food. Tableside blowup between my dad and older sister, Avital. My mom, so upset that she left to take a walk in the rain.

Torah reading in shul the next morning started okay—until my five-year-old sister, Eliana, wandered over to me in the middle of the fourth aliyah and barfed onto my Shabbos shoes. I took a break to clean up but never really recovered. And when I eventually backed away from the bimah, relieved to be done, some random congregant coughed into his hand, pointed at me with his cane, and told me that I was “Nu, a little flat.”

And then there was the Sunday party held at the Bergenville Hotel and Convention Center, Ballroom C. (“As in Chaim,” my cheesy uncle joked.) So close to the New Jersey Turnpike that you could smell the exhaust from passing cars. Some gross food, mostly leftovers from shul lunch the day before. My friends, trying (and failing) to pump me up. And then my speech, which was . . . fine, considering I put zero effort into it. Not that it would have mattered either way. My parents didn’t hear a word. My dad spent the whole thing hunched in a corner, faced away from me, busy yelling at Avital for whatever it was she did this time. And while my mom was technically within earshot, she spent the speech with her head flamingoed under our table, trying to pry my littlest sister Esty free from one of the legs.

According to the bar mitzvah invitations, this weekend was supposed to be about me. But I’m also the middle kid of five kids, so you do the math. I could have skipped the speech and recited the ABCs at the podium instead. They wouldn’t have noticed. At least I was now thirteen, which meant that I was almost in high school, which meant that in only a few short years I could leave for yeshiva and not spend every waking moment being completely ignored. I was counting the seconds until my life could finally be about me.

Hence my approach to the weekend: Just get through it. Just get past it. I barely said a word at Friday night dinner. I sped-read the parsha like my life depended on it. And I spent most of the Sunday party stealing glances at the clock on the wall, counting the minutes until I could put this whole annoying thing behind me.

Speech over, I got a unanimous round of applause, bursts of “Mazel tov! Mazel tov!” from the crowd. So not a total loss. A little more dancing and the bar mitzvah would be over. One more box checked on the way to my real life.

I smiled, took another look at the clock, and—

My second bar mitzvah went weird, mostly because it happened again, same as the first. Friday night dinner. (“Avital, you need to have more respect!”) Torah reading in shul on Shabbos day. (“Nu, a little flat!”) Sunday party at the hotel, Ballroom C. (“As in Chaim!”) I pushed away the panic. The only logical explanation was that I’d had a vivid, semi-prophetic dream on Thursday night. I chalked it up to nerves and talked myself into believing everything was completely normal. My brain knew I’d been dreading the bar mitzvah. And it wasn’t like the details were that hard to predict. Avital and our dad had been squabbling for weeks. Mr. Bendish—a cranky old man who complained in shul about everything— probably hadn’t liked a Torah reading since 1975. And Uncle Chaim made terrible puns all the time.

The real miracle of the occasion would have been if my parents had remembered that, yes, they did have a kid named Ezra and, yes, it was his bar mitzvah this weekend. By lunchtime Sunday, I’d convinced myself that I was imagining things. Just the bar mitzvah jitters, ha ha. Perfectly natural. We ate our crusty food. I gave my big speech. The crowd chirped their chorus of “Mazel tov!”—and then I blinked, reset, and woke up in my bed on Friday morning, like the whole thing had never happened. Again.

My third bar mitzvah did not go great. Friday night dinner. (“AVITAL, YOU NEED TO HAVE MORE RESPECT!”) Torah reading. (“NU, A LITTLE FLAT!”) Sunday party, Ballroom C. (“AS IN CHAIM!”) Breathe, Ezra. Breathe. I kept rapid-fire asking my parents and siblings what was happening, why they were playing this cruel joke on me, if they were also reliving my bar mitzvah over and over.

They were not.

“Are you sure you’re okay?”

“Let’s take your temperature.”

“I think the stress must be getting to him, Yosef.”

Every reaction except “Yes, of course we believe that you keep repeating this weekend and no one else seems to notice but you. How can we help?”

They weren’t listening. They couldn’t hear what I was trying to say. What else is new.

For the speech that time around, I really let them have it:

“What is wrong with you people?! Can’t you see that something strange is going on?! Imma, Abba, you’re supposed to take care of me! I know you’ve got four other kids to worry about and don’t usually have the time for little old Ezra. But you’d think that on my weekend, you’d listen to me. You think I like this? You think I want to be stuck here with all of you?! I can’t wait to get out of here. And another thing—!”

At least I finally got their attention for three whole minutes. My dad and Avital took a time-out from their argument to stare at me, mouths open, chins on the floor. My mom let Esty alone under the table, my shrieking louder than her cries. My older brother, Eitan, was standing in the back, motionless with horror, pitcher tilting out so much soda into his glass that it spilled over the top, waterfalling over the rim of the bar—like he was the one frozen in time and not me.

Five minutes in, Uncle Chaim gently tried to remove me from the stage. I threw him off, pressed my palms hard against my temples: “YOU ARE NOT FUNNY AND YOU HAVE NEVER BEEN FUNNY AND ‘C, AS IN CHAIM’ ISN’T EVEN REALLY A JOKE! IT’S JUST A LETTER AND YOUR NAME! THAT’S NOT ANYTHING! ANYTHING!” No one was safe. Not Mr. Bendish. Not my parents. Not my friends. I got everything off my chest. Roasted the lot of ’em. What did it matter anyway? They wouldn’t remember a thing.

Sure enough, the clock struck 1:36 p.m., and it happened again. And again. And again.

So welcome. Take a seat. Thank you for coming. Today, I am a man. And also yesterday. And tomorrow too. What’s the difference? Who’s got the energy to be mad about things that never change? I’ve spent most of the last dozen bar mitzvahs in a fog. Going through the motions. Mouthing along to words I know are just around the corner.

Always: “Avital, you need to have more respect.”

Always: “Nu, a little flat.”

Always: “Ballroom C, as in Chaim.”

Always on Friday night, Eitan steps on Eliana’s LEGO mess and breaks the skin on the bottom of his foot. Always on Saturday night, Avital sneaks my dad’s car without telling him, caught in the act when she gets back home. Always right before the Sunday speech, my mother ruffles my hair and says, “It’s not every day our baby boy has a bar mitzvah.”

Now that’s a funny joke.

This has got to be—what?—the fifteenth time around? Twentieth?

I stand and shuffle to the front of the crowd. There’s my dad, right on cue, cornering Avital (“No respect.” “No respect.” “No respect.”) for last night. Here’s my mom: “It’s not every day our baby boy has a bar mitzvah.” Esty squirms to the floor and starts to cry, clutching a table leg for dear life.

“This week’s parsha,” I start, my voice dull (and “Nu, a little flat.” “Nu, a little flat.” “Nu, a little flat.”). I recite the words and stare at some spot on the opposite wall, my eyes glazed over.

Ballroom C (“As in Chaim.” “As in Chaim.” “As in Chaim.”) is like all the other ballrooms on this side of the hotel: just a section of a larger room, divided into thirds via fake walls. I’m up on a raised dais, facing a small dance floor whose scuff patterns I know like the back of my hand and a dozen circular tables filled with friends and family who are not nearly as tired of this day as I am. I glance at the clock on the wall: 1:30 p.m.

Almost over.

Never over.

Make it stop.

And then a door opens. Across the ballroom, a kid wanders in, silhouetted by sunlight beaming in through nearby windows. Once through, he sticks out like a sore thumb. His clothes, for one thing. Jeans and a hoodie. No yarmulke. Mostly, though, I notice him not because of what he’s wearing—but because he’s here at all.

Someone new.

I trip off the stage.

“Is everything all right?”

“Give him some space.”

“Do you need water?”

I ignore them. Begin to run. But halfway across the room, I trip again, fall to my knees, raise my eyes back to the clock. It’s too late.

The kid is still watching, still staring, now holding up a handwritten sign in the back of the room. Sharpie cap in his mouth, a smile blooms at the edges of his eyes. The poster board reads:

I KNOW YOUR SECRET.

MEET ME YESTERDAY.

And then it’s 1:36 p.m. and I’m back to the start.

✡️

Joshua S. Levy is the author of several middle grade novels: SEVENTH GRADE VS. THE GALAXY and its sequels (EIGHTH GRADE VS. THE MACHINES and LAST SUMMER IN OUTER SPACE), as well as THE JAKE SHOW, released in May 2023, and FINN AND EZRA'S BAR MITZVAH TIME LOOP, released in May 2024; he is also co-editor of the middle grade short story anthology, ON ALL OTHER NIGHTS, which released in March 2024. He's received two Sydney Taylor Honors (for JAKE and FINN AND EZRA), a National Jewish Book Award (also for FINN AND EZRA), and a hand-drawn "Best Dad Award" mostly for (according to his daughter) his excellent robot impression.

Josh lives with his wife and children in New Jersey. Visit him online at www.joshuasimonlevy.com.

✡️

Five Tiny Delights

Light roast coffee

The sound a ring of keys makes when tossed in the air

Cylinder seals

The cosmic crisp apple

Star Wars gifs

✡️

Five Tiny Jewish Delights

Purim on a Sunday

Not having to re-read my bar mitzvah parsha every time it comes back around

Matzah and cream cheese (which, every year, I swear I'll continue to eat after Passover and then never do)

Debates about the origins of the family name "Hasmonean"

That bit about Maimonedes and lemon cakes

✡️