Jewish Today: The Poetry of Philip Terman

Welcome to the beautiful world of Philip Terman's poems. Beauty yes, but also bucketfuls of compassion, of love: for family, for tradition and for the poet himself.

Saint Esau Hast thee but one blessing, my father? Bless me, even me also, O my father. And Esau lifted up his voice, and wept aloud. Genesis 27: 38 I came out red, as if embarrassed to be alive. * Though, like anyone, I wish I could identify with Jacob, who, after all, had his name changed to Israel, and whose twelve sons began the great tradition, and who was buried among the Patriarchs— if I was honest with myself, I would have preferred tramping outside among the deep breathing animals, the dew-laden grass, perhaps a full moon, the distinct stars, chanting songs in the open air— me with my hairy body, my rough skin, me with my restlessness, my impatience to settle in one place, me with my father-love, with my hunger: like anyone, I wish I could identify with Jacob, but more likely I would have exchanged that intangible promise, that fantasy of future fame, for that cooked meal, that sumptuous stew. * Esau, I too, wear a hairy garment, inherited from my father, that gorilla, who—not the way the old men in the synagogue beat their fists against their tallit on the day of atonement—bore and pounded his chest and roared and roared until I would crackup at this mountain of an animal. And when he returned from wherever the day wore away his eyes, he would belch and ravish the sweet meat and rise full-length, curly hairs brushing the ceiling. * I donned the same fitted suit I wore in court for my hearing as I wore in the synagogue on the Day of Atonement. I was convicted: in court of a crime. in the synagogue of a sin. In court I apologized to the victim. In the synagogue I apologized to God. I acknowledged my misbehavior and received my sentence before witnesses: In court: the deserved penalty and a hope that I have placated the victim. In the synagogue: a fast, a beating of my fist against my heart, a prayer to be inscribed in the Book of Life. * Dawn. A man of the field, like this field—sun rising and illuminating the half-moon, the apple blossoms I’m sitting under and taking in, the nest-builders hard at work and singing—I did not don the cap and scarf and say the Modeh Ani that thanks God for the return of my soul to my body and allows me to live another day. Or, if I did, it was this silence and birdsong, these words that appear as prayer. * Dear Rashi, why do you hate me? Is it because I have no time to don the cap and scarf, to figure out which direction is east and bow and sway? A bit of a brute, I admit, unrefined, uncouth and, yes, it’s true, I still spill coffee on my shirt, refuse to trim my hair, my bushy eyebrows, play music too loud, act on a whim. I still fill a room with my bulky body, get overexcited, speak out of turn. With all I could carry I approached the one who tempted me because I was famished, and thoughtless, and neglected my loved ones and so I was denied my rightful place at the table. Though I swore I would kill myself, each morning I chanted David’s psalm: You will not despise a contrite heart— * I was not ready to chant the Kol Nidre, yet nevertheless I was called up to stand before the open Ark and find within myself the voice that was required of me, the voice hidden in the deep down, below my errors, my words spoken in haste, my actions taken without thought, the hurts I caused. The fast had begun. The Ark opened, the scriptures revealed, the worshippers risen in their white garments, the rabbi nodding: it’s time/ And, though I was not noble, or virtuous, and though my wrongs were a weight I could barely hold, the way, at the dawn of my adulthood— almost another lifetime ago, my muscles tightened to lift the Torah and carry it around the shul, pausing at each row of pews for the congregants to touch the scrolls with the fringes of their tallises then their tallises to their lips— something about the circumstances of my life brought me to face the sanctuary and the souls who stood waiting for me to confess release from our flaws, and rejoice, with trembling.

My Grandfather Reading The Forvitz How far I am from the old language. Each night, after my grandfather came home from selling scrap, he’d wash the dust out of his hands, sit at the table, complain the soup was too hot then retire to the couch, the daily news spreading its wings over his head not like the shawl he and my grandmother stood beneath that moment that sealed all our fates. Sucking hard candy, he’d read slowly, right to left, consulting the personals in the hopes that a few familiar names from that obscure village that no longer exists made it across and placed an ad so my grandfather could sponsor them and usher them into their new lives. Why not? Don’t miracles happen? Why not on 158th and Kinsman? Why shouldn’t out of that nightmare something wonderful appear?

Bat Mitzvah Sonnets for My Chinese Daughters

1: For Miriam Xinxiu*

A promise, a choice, a carrying forth,

an inheritance, what’s yours to receive

and pass on— your portion of this book,

these words, this story, these questions,

these rituals, this bread, this wine, the candles,

the blessings, the days of remembrance, this new star,

the mournings, the joys, too, especially the joys,

the celebration of your very own self—

to know that when you are most alone, you are not alone,

there is this presence, nameless, secretive, sacred,

this sensation of something other than yourself,

deeper than your sorrows—oh child, oh young woman,

clothing your years in adulthood, chanting

this ancient tongue, entering this song.

2: For Bella Xiaolu**

Brief and beautiful as morning dew,

streak of sunlight, bluebird flash,

candle flame, quick dream, here-

and-gone-again-hummingbird, now-

you-see-it-now-you-don’t deer.

Childhood, how long?

These faces, particular

and distinct, historical and spontaneous,

in mystery and discipline, the way

we are gathered here, written down,

beyond reason. How did this moment

find this girl and transform her into

a woman? Quick as a small deer,

mysterious as morning dew.

*Xinxiu: “new star”

**Xiaolu: “small deer” and “morning dew”My Taharah Philip Shalom Terman Will still be my name, for does losing a life mean also losing the one name we’ll always be known by? The sacred society inspects for bodily fluids, blood, wounds, abrasions, clip my nails of fingers, toes, the ones my wife kvetched about when they accidently scratched her in the night. Lying on the steel cot, my head elevated on the headrest— they will inspect my receding hairline, the pencil stab on my forearm from elementary school, my outie belly button, the cyst protruding from my neck—my kids called me Shrek and insisted I get it removed— my chest so hairy they compared it to a bear’s when they would hop on my back and and I would stomp across the living room and neigh like a horse and roar and roar. Bodies, the director says: are always heavy. All that weight. I broke some commandments and sunk down deep and worried would my name be scribed in the Great Book and was I worthy of those years, did my soul work its way into atonement— but as they begin washing me back into the purity in which I first appeared, I will again become holy. In silence, in gowns and rubber gloves, they fill the blue buckets and pour over me the water, starting at the head, precisely, as in a garden, down to my feet, then from my feet all the way up to the tip-top of my head, washing every inch of me, the public and private parts, the chorus of washers intoning: He is pure. He is pure. He is pure— then the careful drying, the rabbi chanting the blessing: Grant us the courage and strength to properly perform this work, dressing me in the tunic, inserting the arms into each sleeve, straightening, no slack, the pants, pulled over the feet, one leg, turning me to the side, the other leg, the undershirt, the shirt, the hood, the cloth to cover my face. Finally, the garter belt, passed under me, wound around my frame and woven into a knot in the shape of the Hebrew letter: shin: for Shaddai, Almighty God. Will they remember to retrieve the small package of sand ordered from the Holy Land, commanded to place beneath my pillow, my portion of the eternal? They strap me in the hydraulic body-lift and the director cranks me up towards heaven like a swallow and slowly sets me down snugly into my pine house where I will seep into the earth from which I came. The rabbi taps the roof and insists: He must face East. And so they secure the Jewish star atop the head-end to alert the gravedigger in which direction plant me. Silence surrounds us. Now they softly chant a plea to the angels: in the name of the Name, and all around surrounding him. Opening their eyes toward each other.

Philip Terman’s most recent books of poetry are My Blossoming Everything (Saddle Road Press, 2024), The Whole Mishpocha (Ben Yehuda Press, 2024) This Crazy Devotion (Broadstone, 2020), Our Portion: New and Selected Poems (Autumn House, 2015) and, as co-translator with the Syrian writer Saleh Razzouk, Tango Beneath a Narrow Ceiling: The Selected poems of Riad Saleh Hussein (Bitter Oleander, 2021). His poems and essays have appeared in journals, including Poetry Magazine, The Kenyon Review, Tikkun, The Sun, The Georgia Review, Poetry International, and anthologies, including The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Poetry, 101 Poets for the Next Millennium, Blood to Remember: American Poets on the Holocaust, and Joyful Noise: An Anthology of Spiritual Literature, Extraordinary Rendition: American Writers on Palestine. Retired from Clarion University, he served as co-director of the Chautauqua Writers Festival for 14 years. In 2023, he co-directed the James Wright Poetry Festival. Currently, he directs The Bridge Literary Arts Center in Venango County, PA and is co-curator of the Jewish Poetry Reading Series, sponsored by the Jewish Community Center of Buffalo. Recipient of the Anna Davidson Rosenberg Award for Poems on the Jewish Experience, Terman conducts and coaches poetry workshops hither and yon.

https://philipterman.my.canva.site

5 Delights

1). Planting corn seeds in early June

2). Unleashing dog Zabar and watching her run into the open field

3). Pressing my nose against the first Madonna blossoms of spring

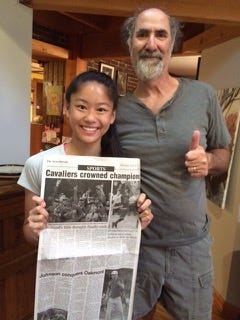

4). Sharing the ecstatic pleasure of the Cleveland Cavaliers beating the Boston Celtics with my daughter, Bella

5). Fresh everything bagel with lox, cream cheese, slice of red onion, dill pickle on the side

5 Jewish Delights

1). Being called with my wife to the Bimah for an Aliyah

2). Braiding challah

3). Performing acts of Tikkun Olam: my correspondence with my poet friend who lives in Gaza

4). Memories of my mother lighting the Sabbath candles

5). The pleasure of watching Seinfeld with my daughter

There are really no words for how much I love these poems. I'm so honored they're here.

So enjoyable to read these. The lovely details described in My Tahara. "He is pure" reminds me of the morning prayer that says the soul you have given me is pure. The final return of the soul.

My Grandfather Reading the Forvitz reminded me of my father describing how his father would also read it aloud, after work, in the kitchen as my grandmother cooked. He only had a third grade education in Odessa. Same with my grandmother but she was proud of being able to read War and Peace in Russian. My father spoke Yiddish too, then it was lost. Thanks for this post.