This magazine was named for Judith Aftergut Meller, of blessed memory. Both of my parents worked full-time my entire life, so when I was very little, other people took care of my brother and me during the day.

Judy was a child survivor of Auschwitz. She was orphaned at age 13, when her mother and father and all her brothers and sisters died at the hands of the Nazis. She was the sole survivor within her family.

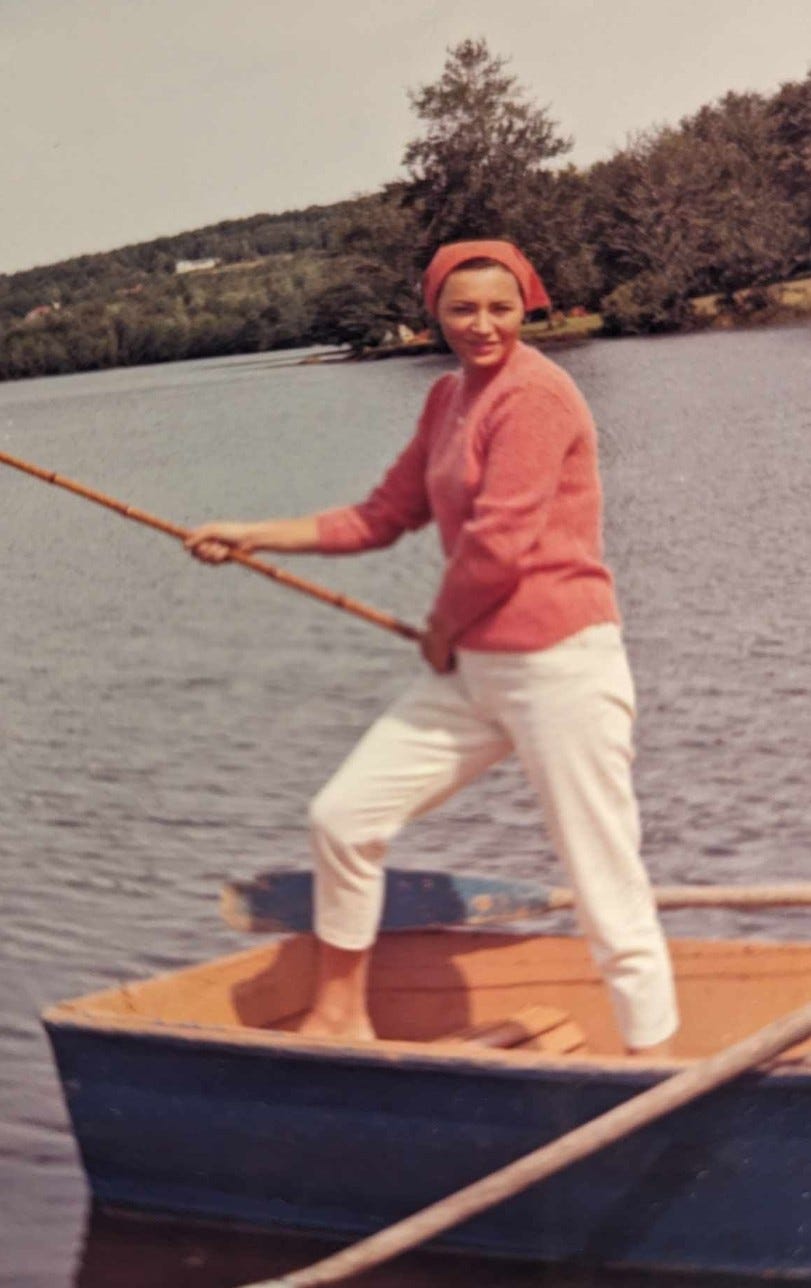

She was a stunningly beautiful woman. Here she is in early adulthood:

And here she is many years later, as beautiful as ever, with me and her younger daughter.

Judith started telling me her story when I was two or three, long before I could comprehend it. She told it to me over and over throughout my formative years, and to anyone else who would listen, thinking that would make a difference the next time. As a very young child, I absorbed it much as I would any other cruel and outlandish fairy tale. It didn’t seem so different than, say, the story of Hansel and Gretel. Villains existed, and they put people into ovens. I understood from an early age that nothing was too terrible to be true.

Even though the Nazis murdered her entire family, she harbored no particular bitterness toward Germans or Germany. She told me the potential for that kind of evil is in every group of people on the planet. I think of her every day as I see that evil all around me today, in so many different forms.

When you imagine people from mid-20th-century Europe, intellectually you know they were just like us, they lived in color, they had the same sensibilities and emotions and intelligence.

But if you’re anything like me, part of you doesn’t really believe that. You think of the black and white footage from those years, and on some irrational level, you believe they were black and white people living in black and white TV land. They weren’t really like us.

In that spirit, I always wondered: who on earth were these “friends and neighbors” of the Jews, who turned their heads in response to what was happening? I could never have friends like that!

Please believe me when I say I would have very much preferred not to now know otherwise. I would have been very happy to live the rest of my life without finding out which of my friends would have made perfect good Germans.

I also wondered how so many intelligent people could have fallen for Hitler and his hatred. There’s this old liberal saw that bigotry is an affliction of the uneducated and provincial – that once you meet real people in a hated group, you can’t hold onto that hatred, and that once you learn to think critically, you’re not vulnerable to propaganda.

But what’s happening in our most prestigious universities all across the country puts the lie to that notion. In fact, the highly educated seem especially prone to parrot flagrant lies about Israel and Zionism.

Often these days, I feel like it’s simply and irreducibly the Jewish fate, in every place and in every age, to see with our own eyes and experience within our own lives exactly how it happens.

At any rate, on the day Judith escaped from Auschwitz, the infamous Dr. Mengele had just consigned her to the gas chambers during the morning selection. She was so thin by that time that he lifted her off the ground with one brutal fist closed around her neck.

While she was dangling there, hanging from his hand, she looked straight into his eyes – eyes she described as black and dead, flat and inhuman as the eyes of a shark -- and every ounce of her ferocious will was suddenly funneled into a marrow-deep, overpowering, visceral conviction.

She thought: You… you!... you will not be the death of me.

She was thirteen years old and shivering and skeletal, and the Angel of Death had her by the throat, and still she managed to feel — above all other emotions — a wayward and blazing contempt. I could well imagine those words running through her head, in a tone like spitting.

You… will not be the death… of me.

She escaped that very hour. When he flung her to the left, the side consigned to death, she managed to dart behind him and bolt into the surrounding crowd. She was so thin that she easily disappeared into the chaos of Auschwitz, wending her way into a prisoner regiment leaving for a labor camp.

*

I adored Judy beyond words. She only took care of my brother and me for a couple of years, but we remained very close friends for the rest of her life, and regularly visiting her home in Portland during all the years I lived in NYC is how I fell in love with the former city and decided to move here when I had a family of my own.

She helped to found the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, and one of her most painful memories remains etched into its stone wall today. The story was familiar to me: when she and the other children who’d been separated from their families were sobbing, begging to know where their parents were, a guard barked:

“Stop all of your whining! See that chimney, see that smoke, smell that stench in the air? That is your parents!”

I wish I could say that she knew comfort and ease once she was liberated by the Allies, but she weathered a series of staggering hardships throughout the rest of her life: marital turmoil, two divorces, motherhood at 18, ongoing financial insecurity, the stresses of single parenthood, a child with cognitive impairments, illness, exhaustion, depression, chronic pain.

In 2004, suffering with terminal cancer at the age of 74, she was among the first to avail of herself of Oregon’s nascent Death With Dignity law. And she declared that choosing the hour and method of her departure was her final fuck you to Dr. Mengele.

*

In My Promised Land, Ari Shavit described Israel’s many Holocaust survivors who went on to have children of their own:

The 30- and 40-year-old parents know they are the desert generation. Though they were saved from annihilation, they know that they will never reach a true haven. For them everything is temporary, fragile, and in doubt. For them life is waiting for the next catastrophe.

But their children are something else... their children are arrows shot to the future. For even though the bow was scorched and deformed in the great fire, it can still shoot a future-bound arrow.

All my life, I had an overwhelming desire to be such an arrow. I was not Judy’s biological daughter, but I was still one of her children and she was one of my mothers. Her older daughter, Rikki Schoenthal, is a cherished loved one with whom I’ve met again and again since the war began. We share the feeling that with us, the line between friend and family is impossibly blurred.

I’ve carried a torch for Judith all my life. I wanted to make her happy; I wanted to make her proud. I wanted to avenge her suffering. I wanted to realize her dreams.

As a kid, I had many ideas about how I would do this. I would become a Nazi hunter like Simon Weisenthal. I would join the Mossad and assassinate terrorists. I would Save Soviet Jewry, as signs all over Jewish Pittsburgh exhorted us to do in the 70s: in my childish imagination, I piloted a plane into the USSR under cover of night, landed on some secret, prearranged Soviet airstrip, ushered refuseniks into the cabin and flew them to Israel or America.

Watching the Sabbath scene in Fiddler On The Roof, I wanted Golde’s maternal blessing for myself: May you come to be… in Israel a shining name…

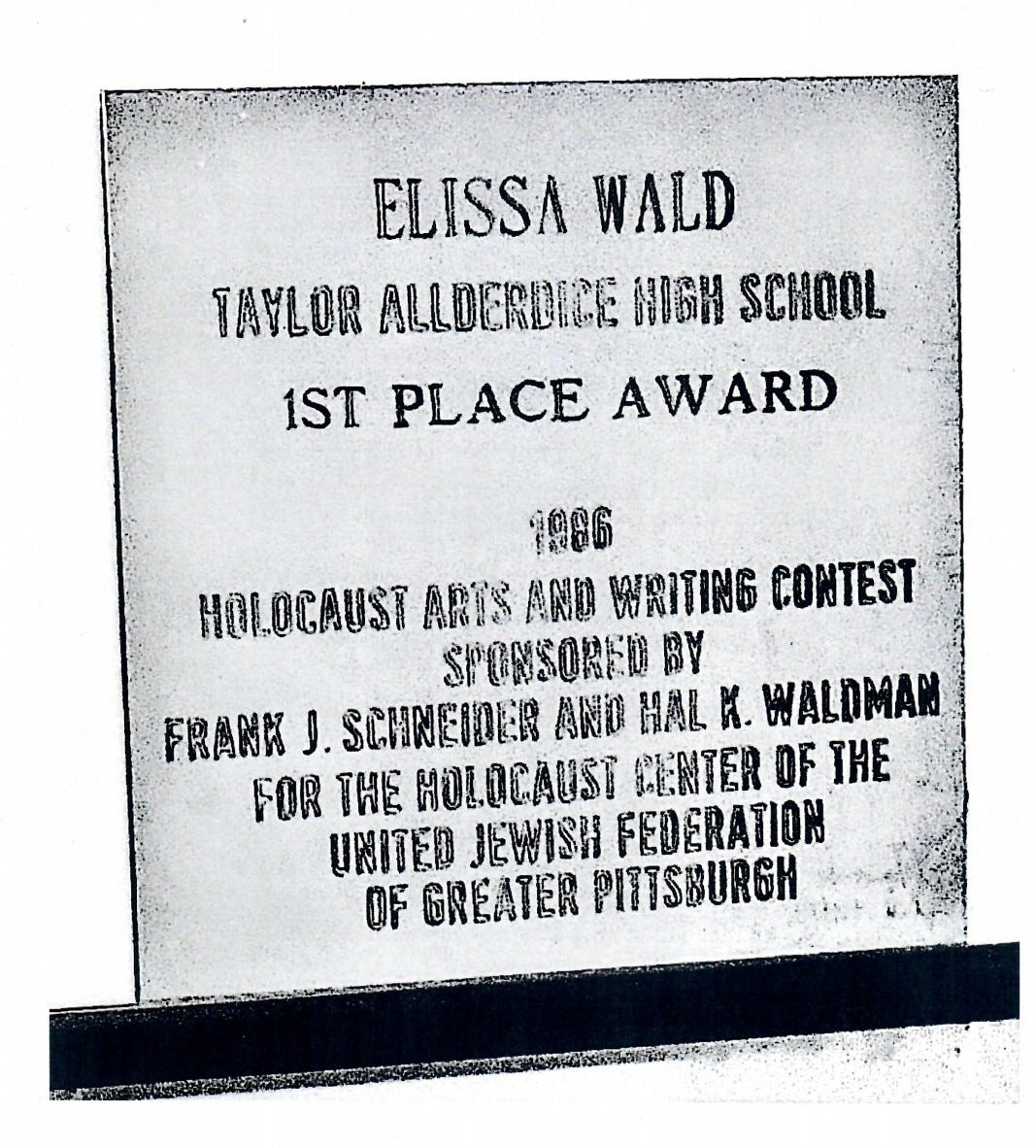

When I was 16 years old, there was a city-wide Holocaust Arts & Writing Contest open to high school students. When I won first place in the writing division with a poem titled Despair in Auschwitz, I felt like I’d won for Judith and the first thing I did was to send her the news and the poem.

A few months later, I also sent the poem – along with the first fan letter of my life – to Elie Wiesel, the (now departed) internationally renowned author of several Holocaust memoirs. Imagine my amazement when he actually wrote back — and with a personal note, not a form letter.

Thirty-four years later, a message from his son Elisha appeared in my Facebook inbox. I’d written a post in defense of Israel and it had been shared many times and he had seen it and been moved by it.

And I myself was moved in turn by the idea that father and son had each written to me, quite unbeknownst to each other and more than three decades apart, and that both of them had said essentially the same thing.

Spoiler: I did not become a Nazi hunter. I did not become an assassin or a stealth pilot. Writing is all I really know how to do and the only way I truly feel equipped to fight for my people. But we all have to work with what we have, and in so many ways, I feel as if my whole life has been leading me to this point. So hineini, here I am.

There is also a secondary meaning to this magazine’s name, derived from the iconic story of Judith and Holofernes. In The Book of Judith, the story’s namesake is a beautiful Jewess who seduces the general of the Assyrian army who has invaded her home city of Bethulia. She is invited to his tent, where she plies him with wine until he’s addled and then asleep, at which point she beheads him, leaving the Assyrian army leaderless and in chaos, and thus saving nearby Jerusalem from being overtaken.

I’d like to think both versions of the name embody the spirit of this publication — the spirit of fierce and beautiful Women of Valor.

Thank you for being part of the JUDITH community. As I wrote in my note to the magazine’s original subscribers, this journal was launched for the purpose of promoting Jews in the literary world at a time when we are under siege within the industry — not just for supporting Israel, which would be bad enough, but just for being Jewish. This has taken the form of blacklists, boycotts, resignations, event shutdowns, and both explicit and implicit refusal to consider Jewish content by agents, editors and publishers. Thank you so much for joining me in the fight for Jewish writers in this harrowing time. We will weather the current moment together and emerge stronger for it — I know we will. It’s what we do.

Am Yisrael Chai.

What an incredible set of stories you've told here. I live in so much gratitude for knowing you, and having been blessed to read your words. You make me want to be brave, too, you and your Judith.

My grandmother was a Holocaust survivor. Her siblings were not so lucky. Several of them are buried in Baby Yar in Kyiv. My grandmother was the strongest person I ever knew. She became a successful lawyer in the USSR and eventually immigrated to Israel. She was the mother to her only daughter (my mother) but also to me, and my sons, her great-grandchildren. Her name was not Judith (it was Ethel). But I would like to believe that she is one of those Jewish heroines without whom the People of Israel would have never survived. I was thinking of her as I was reading this story.