Editor’s Note:

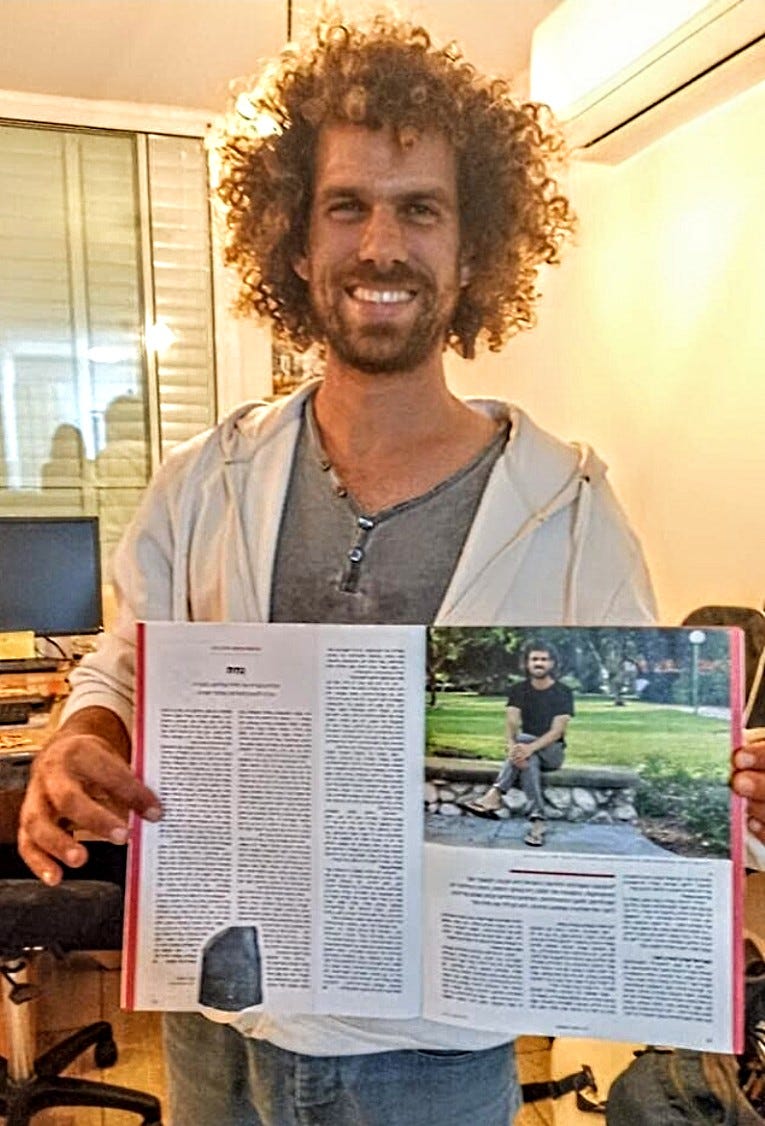

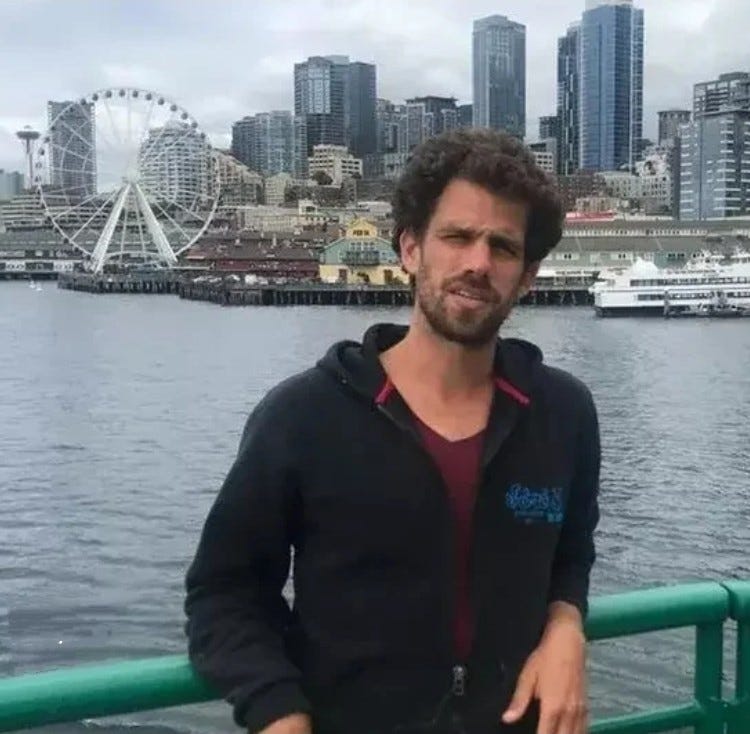

To read about all that Dr. Hayim Katsman (zt”l) managed to do in his thirty-two years is to be astonished that anyone could achieve so much even in a very long lifetime, let alone one cut so tragically short.

Katsman was a scholar, peace activist, writer, mechanic, gardener, musician, deejay, and soldier. He trekked in India and was fluent in Arabic and served as the head of his kibbutz council. He held a bachelor's degree in philosophy from the Open University of Israel, a master’s in political science from Ben Gurion University in the Negev, and a doctorate in international studies from the University of Washington in Seattle.

Still, in spite of all these formidable credentials, the maxim this wildly accomplished polymath abided by in life was: In every room I enter, there is someone smarter than me in some way. And there was something wonderfully feral about him. One has the sense that he answered only to himself in this world, and presented – in any environment – entirely as himself as well, with no use for artifice, conformity or moral compromise.

While every soul lost or abducted on October 7, 2023 is infinitely precious and equally worthy, it’s undeniable that a few individuals – such as Ariel and Kfir Bibas, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, and Emily Damari -- have taken on an iconic status within the Jewish nation. Hayim Katsman was among the victims who became the literal and figurative poster children of Israel: the most widely recognized, prayed-for and/or eulogized and mourned.

If these young people were the children of an entire nation, their surviving mothers have become, in a sense, the mothers of the whole nation as well. Millions of Jews worldwide cling to Rachel Goldberg-Polin and look to her for leadership and consolation. Similarly, in the wake of her son’s death, Hannah wrote in The Times Of Israel, “I realized I had a role to play, a mission if you will. Aside from typical mourning activities like sorting out Hayim’s personal effects… I found myself serving as a kind of container that allowed people to process their own grief.”

When I was in Israel last month, I had the honor and privilege of meeting Hannah and talking with her in some depth, both then and afterward. I’ve also joined – as an ambassador -- the campaign to realize a dream of Hayim’s: to create the only sustainability center in Israel, within the Bedouin town of Rahat, where the residents decided to name the project in his honor.

Hannah talks about all this and more in today’s Jews Of The Universe column.

“Not long ago, I lost the hearing in my right ear, which affects my life in so many ways. I’ve come to think of that hearing loss and my status as a bereaved mother as invisible disabilities. I know most people wouldn’t necessarily think of bereavement as a disability. But what I mean by that is, I can’t really function unless I announce both of these. So I have to announce them all the time to people.

Here’s an example of that. After my son Hayim was killed [by Hamas on October 7th], we had to wait several days to have his funeral. And that funeral ended up taking place on a Thursday, but the day before, I had a medical appointment with an ENT. This had to do with my hearing issue and I’d booked it months earlier. The doctor was hoping to persuade me to get a cochlear implant. I thought a lot about postponing it, but in the end I decided to go.

Another woman accompanied me. She was one of the community members who’d been staying with me during those terrible days. She and her husband drove me across town to the doctor and then she came inside with me.

Just before leaving the clinic, I mentioned that my son had been killed a few days before. And the doctor said she’d wondered why I had someone with me, since I didn’t seem like the type of person who would need to be accompanied to an ENT appointment. But now she understood.”

“Since then, I’ve just told people up front, the same way I ask people up front to talk to me from my left side. So much of my life revolves around Hayim. Like the other day, to break the ice in a group meeting I attended, we went around the circle and everyone had to say what we were doing the next week. And I was going on a grief retreat.

So I said I was taking a trip.

Naturally the next question was where.

I said: Well, up north.

Where up north?

If I’m not intentional about mentioning Hayim’s death up front, a certain tension sets in. Because sooner or later, I’ll be fielding a question like that, which forces a choice. People might be joking around, laughing, and I can either drop this bomb into the middle of the group and totally alter the atmosphere, or I can hold that information back and not bring my full self into the room.

It’s very comforting to be with people who already know, because with them, I can just be myself. And it’s also good to live in Israel, because Israelis deal with death much better than Americans do, and – as opposed to just a regular death in the family – the grief is collective and at the center of everyone’s awareness because of the war.”

“I hate to say this, because it sounds really terrible – but I am going to say it: there’s a certain status to having a family member who was killed on October 7th. And I just try to make sure I’m only using that status for good. Like at my shul, I was on a committee that had to decide how we were going to observe Simchat Torah. And the group decided to have one hakafah [the ritual circling of the bimah and congregation with the Torah scrolls] for people who were killed on October 7th, one hakafah for the hostages, and one for the miluim [reserve forces] families. Then the question arose as to whether we should also have a happy hakafah. And I said absolutely, yes – that we had to have a happy one for the children. The children need to have happy memories of Simchat Torah.

Afterward a woman from the group came up to me and thanked me. She said: Only you could have said that. In other words, if even a bereaved mother can sanction joy, then the question is settled.”

“When Hayim was in second grade, he had this teacher he really admired, and we liked her so much also. She was a great teacher, but he had a dispute with her. I forget exactly what it was, but something to do with an answer on a test. And he was certain he was right, but she was very dismissive; she told him he was being ridiculous.

He was so bitterly affronted by this that he didn’t want to go to school the next day. I understood how he felt, and I was sympathetic, but I had a baby at home and I told him he had to go to school. Then later that day, I took the baby to the park, and I saw Hayim on the street. He was still wearing his backpack and he was just walking up and down on the sidewalk. That park was near his friend’s house and it turned out that he was waiting around for his friend to show up, because then he would know it was time to come home.

Can you imagine a seven-year-old with nothing else to do, killing six or seven hours on the street that way? But he’d lost his trust in the teacher. He had really admired her, but then she wouldn’t hear him out. She wouldn’t take him seriously. So his sense of justice was violated. And even as a little boy, justice was so important to him. And of course his fierce commitment to justice became an enduring theme of his life.”

“Hayim was kicked out of a religious high school because of ideological differences with the staff that couldn’t be reconciled. He ended up in a different school that was also religious, but it had an alternative bent. It was for kids who didn’t need to be micro-managed; it let them work with a lot of independence.

There he needed to take a matriculation exam in literature, which wasn’t a popular subject, so they had to bring in a teacher from the Education Ministry to test him. It was an oral exam, and she asked him the first question. A minute or two into his answer, she cut him off and said, “Okay, next question.” The second question went the same way: again he began a response, and again she said: okay, enough. Next question.

The whole exam was like that. She didn’t let him finish any of his answers. Finally, she ended the exam, wrote “100%” at the top of her score sheet, and said, “Okay, great. The test is out of the way. Now we can talk. I really want to hear what you have to say.”

“I’ve learned so much about Hayim since his death. I’ve learned a lot that I didn’t know. Today I got a phone call from an academic who specializes in a certain Arab country that condemned Israel and praised Hamas on October 7. He got an email on October 13th, 2023 – a few days after the massacre – from an academic who’s in that country’s foreign ministry. Apparently this man had a correspondence with Hayim and considered him a dear friend. Hayim had sent him his dissertation and they’d discussed it. So I just learned that.”

“You know, the President of the University of Washington sent me a personal condolence letter after Hayim was killed. And the governor of Washington did as well. But the president of Barnard College (my alma mater) and its Alumnae Association never acknowledged Hayim’s death in any way, even though they definitely knew about it. I can only presume that was for political reasons. Whereas when my father’s second wife died several years ago, they saw my name in the New York Times obituary and they printed condolences in the Class Notes of their alumnae magazine.”

“It’s well known that Hayim died protecting one of the women in that kibbutz, a woman who survived the slaughter -- and who, in turn, managed to rescue two children that day -- but making that central to his story doesn’t feel right to me for some reason. I don’t want to glorify his death. Protecting others was very emblematic of the way he lived; the fact that it was the way he died seems incidental to me, and not something I’m comfortable highlighting.”

“We’re running a campaign right now in memory of Hayim, who did a lot of volunteer work in the town of Rahat, which is actually the only Bedouin city in Israel. It’s in the south and I went to visit and spoke with the director of the community center spearheading the project. The project’s goal is to build the first sustainability center in Israel. There are four elements: sustainable urban agriculture, cooking, reducing consumption and climate education. It will serve Rahat primarily, but it will also serve the larger community around it. Schoolchildren from Israel will visit on field trips.

There are a lot of cooperative projects that the Jewish communities around Rahat partake in, to benefit the Bedouin community, which is economically disadvantaged. These include food reclamation and initiatives like that. And they told me that on October 7th -- when Rahat was not attacked by Hamas, but the surrounding Jewish communities were – a lot of Rahat residents went to great lengths to help their Jewish neighbors, risking their lives to whisk them to safety

And now they’re all for naming this community garden after Hayim. It’s a big deal for a Bedouin community to name a Rahat-based initiative after a Jew. But Rahat doesn’t exist in a vacuum and neither do the Jewish communities.”

“This past week a woman called me. I got to know her because she has posted about Hayim, about her joy and sadness from reading about him and seeing his picture, and then a mutual friend introduced us. I’ve been in touch with her since. And she decided to become an ambassador for the campaign.

But she had a lot of trouble. It wasn’t easy. First she sent the information to her family and most of them donated but one didn’t, because this sister had lost people who were very dear to her in the Nova massacre. And this woman said to me: I understand it, and I don’t blame her or judge her, but right now my sister’s heart is closed, and yours is open.”

“Hayim identified as a Zionist, even though his form of Zionism was nothing at all like the Zionism of many other people. He took a lot of actions that you could describe as Zionist: he helped revive a kibbutz, he was in the IDF’s Advance Guard, and he stayed in Israel and worked the land. But his vision was a shared land. As the Rahat project’s site put it: he dreamed of a better Israel — one rooted in justice, coexistence, and care for the earth. His life was about creating connections across divides. He played Arabic music as a DJ, built community gardens in Rahat with local residents, and worked to make academia more inclusive. His life’s work was a bridge — between Jews and Arabs, people and the planet, the center and the periphery.”

“A lot of the campaign ambassadors share my concern and grief over the current Israeli administration and all that’s happening in Gaza. It’s very hard to read the news. And a couple of them have told me how healing it’s been for them to be involved in this campaign and do something to build -- not only a worthy initiative in a vulnerable and too-often-overlooked community in Israel, but also build relationships between Israelis from all walks of life. Because that’s what Hayim did. That’s what he was about; that was the essence of his spirit. His vision of Israel was one of love, collaboration and friendship between all the different communities within her borders, and those outside of it too.

On a recent visit to the project site, I was talking with a Bedouin woman when she broke off to point out the butterflies.

You know, she told me, I used to tell Hayim that my dream was to one day see butterflies in our garden.

And he smiled and promised me: yes, there will be butterflies.

And now there are.”

✡️

Please join me in supporting the Rahat Sustainability Project in Hayim’s memory and honor! To learn more and make a contribution of any size, click HERE.

“I realized I had a role to play, a mission if you will. Aside from typical mourning activities like sorting out Hayim’s personal effects… I found myself serving as a kind of container that allowed people to process their own grief.” Oh my goodness how she has taken on so much and I am sure has been a light to so many who like her have suffered from such unsurmountable loss. In addition this idea that her grief is like an invisible disability just about gutted me. That was powerful & caused me to pause and place my own downward head into my own hands and not only pray for all those who grieve, but to pray for Israel that has suffered so very much. This is a powerful piece Elissa. Thank you.