“Last night, just before I went onstage, I received a very hateful message from someone I’ve known since high school, with whom I was very close. This is a guy who was like a brother to me. And he went on this whole rant about me being, you know, the worst kind of white person — a Zionist, a white supremacist. It was pretty awful. I thought I’d kind of gotten to the point where I wasn’t as hurt by these things, but it just crushed me.”

“I grew up a reform liberal Jew on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. My parents were both public school teachers who carried Channel 13 PBS tote bags and shopped at Zabar’s, but the twist was that the Upper West Side was a very diverse neighborhood back then. My parents actually bought a brownstone here in the 60s, and we lived in the neighborhood when it was still developing.

So my childhood friends were all very diverse: many Latin (Dominican and Puerto Rican) families, Black, white – I really had this kind of Free To Be You And Me upbringing and I thought everyone grew up like that. Then I went to LaGuardia, the arts school, for singing, which I don’t really do anymore, but I was a vocal major. And again: the setting was very diverse. All my friends were from different boroughs.

That’s how I grew up and I was always very involved in social justice. My parents read The New York Times every day and that was my life. When I was in high school, there was this kind of rebirth, or golden age, of hip hop -- with Black and Latinos really claiming their heritage and being proud. And I was someone who very much knew my boundaries and I never tried to be something I wasn’t, but they inspired me to look into myself and ask myself, Well, who am I? What is my history?

It was a slow start, but when I went to graduate school for acting in Rhode Island, that’s when I started to feel very keenly that I was Jewish. I was in a kind of culture shock there – I didn’t know how to drive; I was out of the city setting I’d been in all my life. I never felt like I was even all that Jewish until I was in New England. I don’t know if I’d ever even met a WASP before.

In some ways, I was very protected in that NYC diversity bubble. I thought everywhere was like that. So it was a very different world for me. I remember we didn’t have time off for Yom Kippur. And it wasn’t like I was so religious, but I definitely felt some sort of way about that. And then I just noticed that even my energy, my sense of humor, everything – I was like, God, I am so Jewish! I hadn’t felt that so viscerally before.”

“That was when I started writing, and I remember writing this story about a girl who was based on me (though my teacher didn’t know that): a Jewish girl who hung out with all these different people. And after my teacher read this story, she said, “This is not a realistic character.” I was like: oh, that’s so interesting, because I based it on myself. But it didn’t fit her idea of what a Jewish girl was like.

And everyone was supposed to have what was called a “back-pocket monologue” that was really you, that showcased your personality. And I couldn’t find any kind of personal representation in anything. I was a Jewish girl with this urban experience, and I didn’t relate to any stock Jewish characters.

So that was when I started writing. Because then I could create my own stories. And I started getting attention for writing, but I really wanted to be a movie actress. So I got scared that I was being pigeonholed as a writer. At the time, there was much less emphasis on writing for yourself – that wasn’t even really a thing yet.

In my MFA program, I got cast in every role where they just didn’t know what to do with that person. I played a mute; I played someone with no legs; I played an 85-year-old doctor when all I really wanted was to be Juliet: someone pretty and young. I think that ended up really serving me, but at the time, it was hard.”

“When I got out of grad school, I started seeing all these people writing one-woman shows, and they appealed to me. I wanted to write from a perspective that was different from the stereotypical Jewish characters I was seeing — like, for instance, some princess type who went to Brandeis.

I was like: where is the Jewish girl who loves hip hop, who’s friends with all these different people? It didn’t yet exist, and I thought: I guess I need to write that. So I started writing these monologues. I still wanted to be a movie actress, but I thought this would be the bridge.

Then I went to a poetry slam at the Brooklyn Museum, where they were trying out the model for DEF Poetry Jam on HBO. When I saw those performances, I said to myself: you know, I think this is what I was looking for. It was mostly people of color doing these passionate social justice pieces about race. What you looked like didn’t matter much, which was the antidote to the hardest thing, for me, about being an actress: the obsession with aesthetics, and auditioning, and the way you’re typecast.

Discovering a scene where that wasn’t important was so astonishing to me. I could write about what mattered to me, and no one cared what I looked like. And there was a hip hop / rhythmic element to it, which I loved. So I thought: I’m going to try this but with a Jewish voice, which I wasn’t really seeing out there.

The first piece I ever wrote began: Baruch Atah Adonai Viva Puerto Rico Ha’Olam Hamotzi Fight The Power Min Haaretz Amen. It was a mash-up of what I called a prayer of my neighborhood. I had a poem, Culture Bandit, about being a person who went in and out of different cultures.

So I went, I auditioned, I started attending events in the spoken word scene. I went downtown to all the open mics and to the Nuyorican, and then I was just in the scene, and slowly I was realizing that this was truly my thing.”

“So I had this theater background and I was a poet and I wrote this one-woman show called Culture Bandit. I fell into this spoken word thing, writing in this rhythmic way, but I also loved the model of a one-woman show and being able to tell a full-bodied story in that way, mixing music into it. So I wrote that show and I did it at Nuyorican for years.

Culture Bandit was based on my years in high school, being a Jewish girl in the whole Black nationalistic time of hip hop, of Public Enemy and Louis Farrakhan, when I was trying to find myself and my identity. I didn’t think this story was so interesting until I realized no one else was telling it.

So I started that first poem, “You don’t look Jewish…” where I ask, “What does being Jewish look like to you?” I started doing that at poetry slams and getting some attention and being known within the scene.

It was crazy because I would get up on stage and people would look at me with a completely different expectation of what was going to come out of my mouth. But my voice was strong and there was no one else doing a Jewish piece like that, which was unapologetic and quirky.”

“Since then, things have changed and evolved and there have been more Jewish poets, and political poems that – even back then – were anti-Israel, because that was their ticket to acceptance in the scene. And I was the only one who was saying, like, “I’m Jewish and I’m proud.” Not getting into politics, but being proud.

So here I was in this militant Black poetry scene, and I kind of just went in and I’m so glad I did, even though I now wonder whether I changed anyone’s mind. At the time, I felt that I did.

There were so many people in the scene who had never really spent time with anyone Jewish, so just my representation alone was changing something. It helped that people liked the poem, that it was good, and that I wasn’t performing it in this meek kind of way. I held my own, because in slam, the audience is the entity that’s judging you.

The Black community within the scene was very accepting, because I think the expectation was that if a white person got up there, they were going to try to appropriate something that wasn’t theirs. But I was just getting up there and talking about what I knew, and being myself, and I say in that poem, “I’m not trying to compete in a contest of oppression.”

“Then my work evolved to touching on universal women’s issues, which women of all races could relate to. I wrote this one story called Blanquita which was about my dating this Dominican guy. His mother doesn’t understand I’m Jewish and she gives me a crucifix for Christmas. And in the story I put it on and I walk around and I feel like I’m in this costume, this fantasy of being a Catholic girl.

When I read this for Jewish audiences, they often get very uptight about it, without understanding the fantasy underlying it, of removing this one layer of difference between myself and the spoken word community. Because I differed not only in color but also religion. Whereas these Italian and Yugoslavian girls who were Catholic at least shared that bond with Puerto Ricans.

That feeling hearkened back to the era of Madonna, where she sparked a fashion trend of wearing crosses and I always knew: well, I can’t wear that. But there was always the question: what would it be like? And it made Jews very uncomfortable when I would explore that. But people loved that piece, and it really went into the connection I had with this Dominican family.

There’s a Spanish TV show called Sabado Gigante, and the host is this guy Don Francisco. It’s a very popular talk show that’s been on forever and it turns out that this host is Jewish. He’s a Jew who emigrated to Chile and changed his name.

And I wrote about watching that show, which anyone who’s Latin knows about. Latin Jews know that he’s Jewish, but other Latins don’t know it. So I wrote this story and again, there was this overlap between my own culture and the other different cultures I was drawn to.”

“I did this for many years. I was the white girl in the scene. I was there during 9/11 when a rumor went around that Jews were warned in advance to stay home from the World Trade Center that day, and that’s when I started to notice this burgeoning anti-Semitism around me. But I was still committed to staying in the scene and telling my story, and it was one of the greatest things I ever did.

I wrote a bunch of shows, but I avoided the topic of Israel. Whenever it came up, I’d just pray: please, let this go away; please let this go away. But even as it would flare and then die in pretty quick succession back then, I was aware it was there and it wasn’t going to go away.

In the midst of all this, someone hired me to work for Birthright Israel, to help alumni who’d come back from the trip to write about their experiences. It was one of the best opportunities anyone ever offered me, because I’d never been on the other side, directing and coaching, and I wasn’t sure it was for me. But the experience changed my entire life. Because I loved it and I was good at it. So that added a whole new facet to my career, and I loved helping those people.

I created a show that was called Monologues and it was supposed to be for just one night at this Birthright Gala, but we ended up doing it for three years and I’m still very close to the cast that was in that show. And it was more than just, you know, My Trip To Israel. There were pieces about Jewish identity and it was amazing. So I did that and that was a big part of my life.”

“Then I was invited to a poetry event in Washington Heights and a group of Palestinian artists saw that I was being featured at that time. They saw that I had worked for Birthright Israel, and they rallied this campaign of protesting against me, saying to the spoken word community, you know: “How can you be an ally of Palestine and let this Zionist perform on your stage?”

The darkly comic irony was, no one in that scene except me and them even knew what a Zionist was at that time. So no one even knew what they were talking about, and it got no traction. That was in 2008.”

“But then October 7th happened. I don’t know why I was surprised, but my first instinct was to think there would be some sympathy for what had happened in Israel. But there was NONE and I felt it was almost the opposite, that it sparked a little bit of a celebration, and posting an Israeli flag felt very much like an act of rebellion. I could feel that in me.

To be honest with you, I had a spiritual feeling in my body that shit was about to change, and I was going to have to make a decision. And I knew that I needed to be there for the Jewish people. To give my voice and my energy and attention — which I’d been giving to diversity — to the Jewish people. Which was hard, because I knew I would lose people with that.

I learned early that there was no way to occupy any kind of middle ground. I’d seen other people try that and it was a disaster. Because even if the truth is that you support both the Jewish and Palestinian people, if you’re not going to yell “genocide” and the other buzz words, no one cares.

So I was very carefully posting stuff, but nothing intense. I was posting my grief over what had happened. But the spoken word scene was putting on all these events on behalf of Palestine without any mention of the massacre or the hostages at all. So the absence of that began to affect me. I started to feel inspired by other Jews who were posting, but I still didn’t feel ready to say much myself yet.”

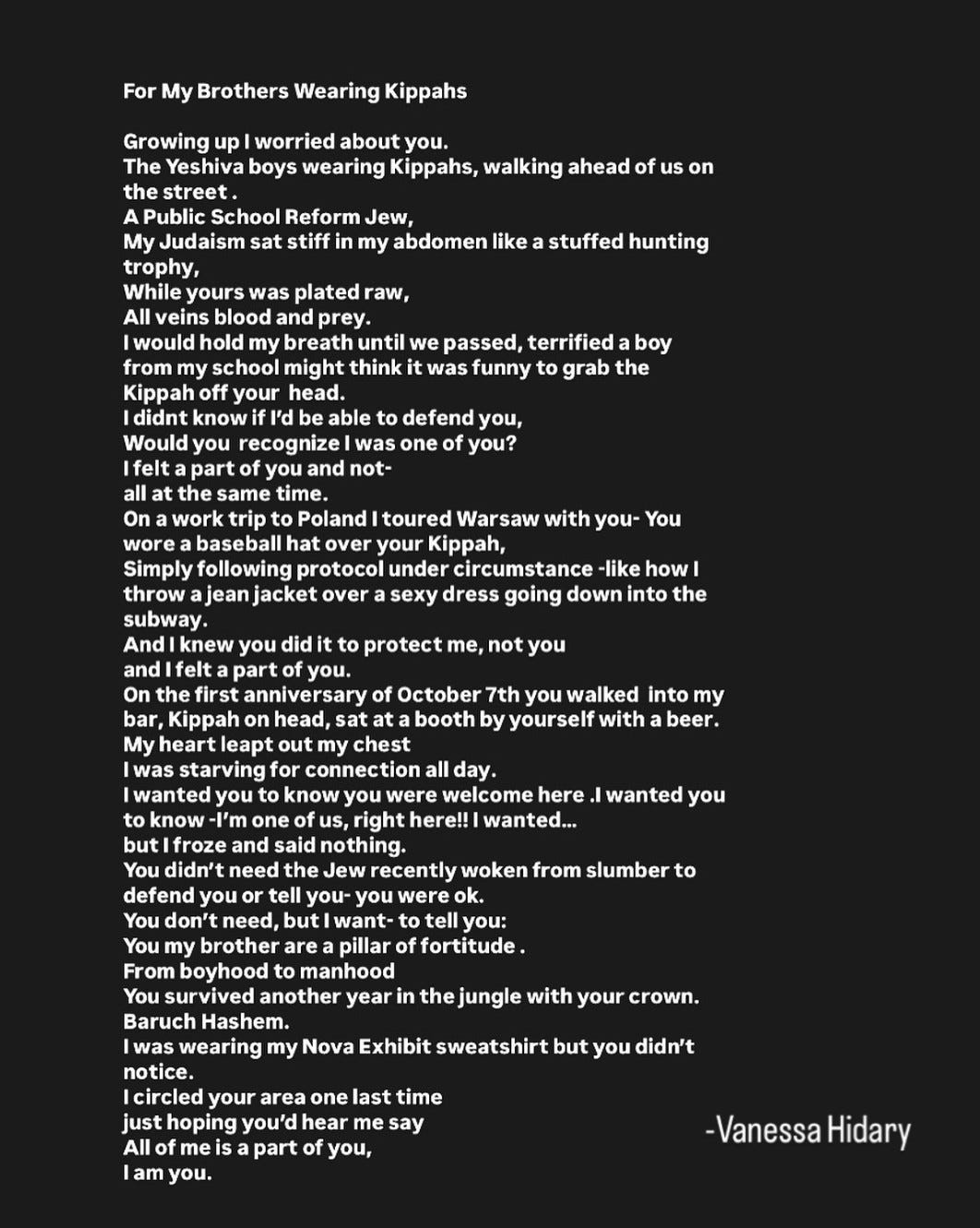

“Then I was asked to perform at an anti-semitism / pro-Israel rally in Vancouver, BC. I felt it was time to make some kind of statement. After doing that, I noticed that people were unfollowing me, notably some women in the scene whom I very much admired.

There were social media posts with some discussion of: oh, there are all these undercover Zionists in the scene! And these probably didn’t refer only to me, but I took it personally. It was very difficult.

Another longtime friend asked me why I was posting about Israel, not about Palestinians. People were very angry at me and I was so upset, even in disbelief that it was happening. But slowly I became a little more bold and started connecting with old friends who were feeling the way I was, so I had some kind of community.

Then I went to Israel last June and it was amazing – one of the most amazing trips of my life. I went with the Jewish Education Project and toured Kfar Aza, the Nova festival site. It made me feel the importance of documenting what’s happening. I felt it was a responsibility that I wanted to take on. And that solidified the decision I’d made to be vocal, but I was still very scared of publicly calling myself a Zionist.

I wrote this poem “Bad Jew” and performed it in Tel-Aviv , with the intention of never, ever performing it in New York, or releasing the video. When I came back, I watched the video every single day and consulted with people I trusted. I asked them, what do you think?

To be honest, I had Jewish friends who were scared for me. But I have to sleep at night and know I’m doing what my heart is feeling and saying. Sometimes I surprised myself with how passionate I was – at how strong and immediate my passion felt. It made some people feel that I had changed or maybe even deceived them in some way.”

“I wrote this piece last week about how I’ve gone in so hard for every other culture, every other group, every other minority, and I’m so happy I did that – that’s me, that’s how I was raised. But as soon as I started putting the same energy into my own people, it made others so angry. And I couldn’t understand why it bothered them so much.

But I’m lucky and so blessed to have a very good artist friend who has become an amazing ally. I actually don’t know whether I could have gotten through this without him. So there are some people like that, but a lot of people aren’t like that. Sometimes I’m still in shock about how much my life has changed. I have a few good friends I just don’t speak with anymore. And it’s painful.”

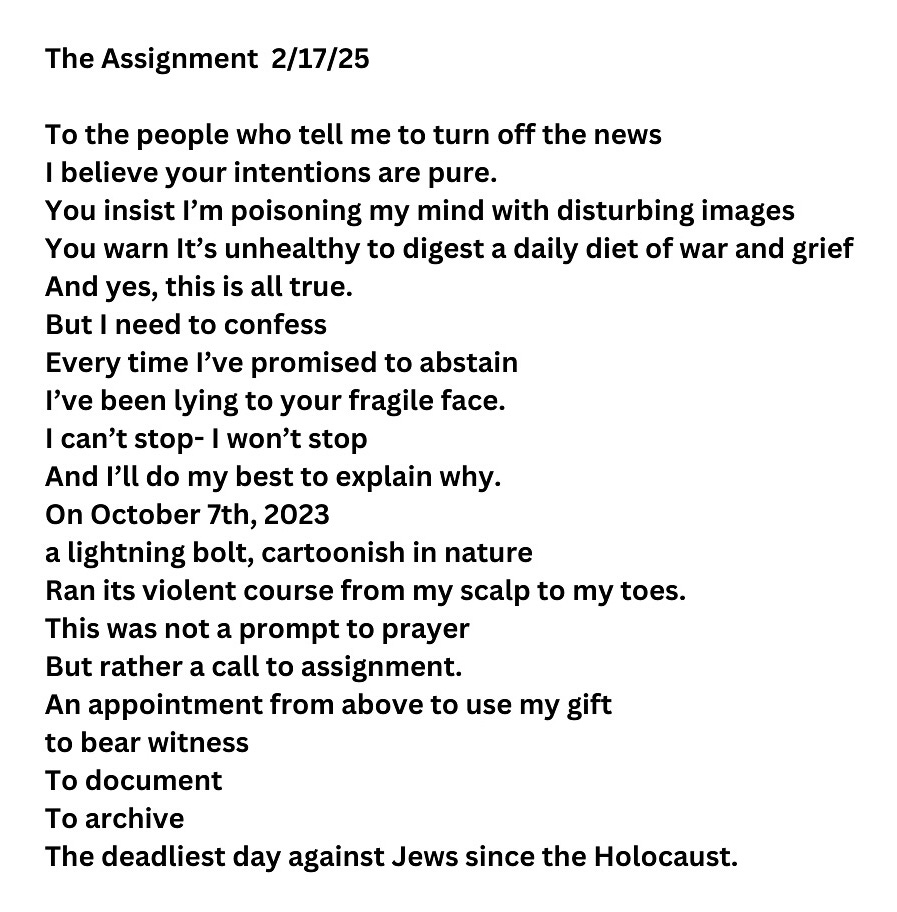

“Recently I wrote a poem called The Assignment. And it’s about how, after October 7th, a lot of Jews experienced something like a religious rebirth, but for me, that didn’t come in the form of feeling pushed to prayer — it came in the form of what I see as an assignment. And that was — is — to use my gifts to talk about my people, and not turn away from that.

I really feel like this is an assignment that’s been given to me. I experienced that conviction as a kind of lightning bolt through my body: that this is what I have to do. And so I’m fulfilling that assignment, as hard as it is.

I’m aware that sometimes people are taken aback by my intensity. And dealing with that kind of reaction — letting them experience that discomfort, and knowing that’s okay — is also part of the assignment. I’m someone who’s very aware of energy, and it doesn’t make me feel good when other people are uncomfortable, but I’m learning to accept it.

In the poem, I talk about people telling me to turn off the news. Because it’s so toxic and upsetting. And I say: you’re probably right, it is toxic and upsetting, and I’m sure that you mean well, but that’s part of my assignment right now. To follow what’s happening, as painful as it is.

It’s not for everyone — I’m not judging anyone who’s not going to sit there and take it all in every day. But for me, in real time, it’s something I’m driven to document. Other people might write articles, or opinion pieces, or songs, but for me, my job is to do it through poetry, with my words. And for that, I need to be paying attention.”

✡️

What an amazing story of awakening, and courage, and commitment, and determination. And identification! It is a personal experience memoir about every Jew, who doesn't even feel Jewish, being reminded of their Judaism. This article is a tide of strength. With people like Vanessa the truth will prevail. From a very appreciative Israeli who appreciates the precaious reality of Jews living outside Israel these days. In my youth movement, we used to say "Chazal ve'ematz" (be strong and have courage), and that is what I wish you, Vanessa.

MY FAVORITE COLUMN. Because Vanessa Hidary, I've loved you for a long time. You are a north star, our Jewish Mamita.